Adam Smith Virtual Exhibit

The University of Glasgow holds the world’s most significant collection of material relating to the life and work of Adam Smith. This unique collection is spread across the University Archives and Special Collections of the University Library. As part of Adam Smith’s tercentenary celebrations, the university hosted a series of exhibits of the material on campus. So that those beyond Glasgow can enjoy the material we have created this virtual exhibit.

In the virtual exhibit you will see images digitised as part of our John Templeton Foundation-funded project Smith@300: Celebrating Adam Smith as Scholar, Educator, and Citizen. Each pillar of the project is represented in a collection of images from Smith’s published work, his correspondence, and records from his time as a student and professor at Glasgow.

Scholar

Title Page of the Lecture on Jurisprudence

Student notes of Smith’s lectures on Juris Prudence or Notes from the lectures on justice, police, revenue, and arms delivered at the University of Glasgow by Adam Smith Professor of Moral Philosophy probably in the academic year 1762-3.[Published 1896].

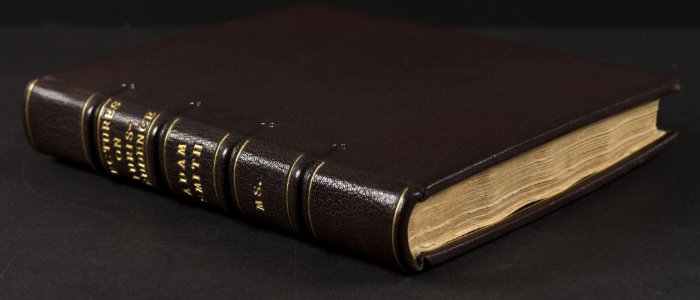

The second set of Lectures on Jurisprudence

These are a variant version of Smith's Lectures on Jurisprudence dated 1762-63. They are differently arranged and often more fully illustrated and explained than those edited by Edwin Cannan. Cannan showed that the lectures contain much of the material afterwards used in The Wealth of Nations.

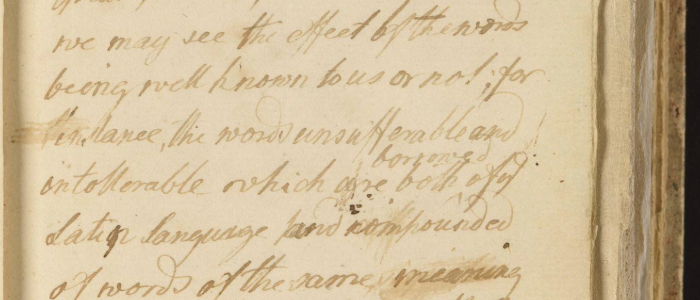

Adam Smith’s Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres

These are an almost complete set of a student's notes of part of Smith's course on Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University given in his last unbroken academic session as Professor there 1762-63.

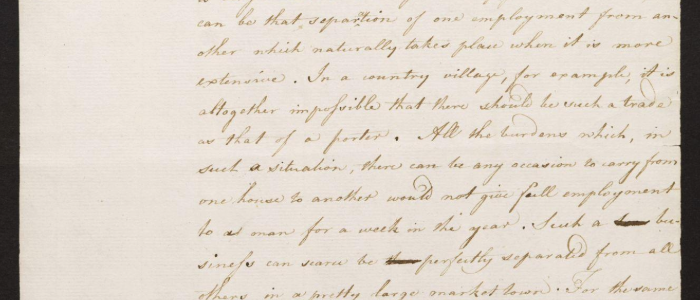

First Fragment on Division of Labour

A very early economic work of Adam Smith. His first discussion of the division of labour is a draft version of ideas that would later appear in the Wealth of Nations, dated circa 1760.

Title page of the first edition of The Theory of Moral Sentiments

The first edition of Adam Smith's first book was published in 1759 and written while he was Professor of Moral Philosophy in Glasgow. The book provides a penetrating examination of moral psychology tracing moral judgment to our sentiments, our capacity for imaginative sympathy with others, and the development of an impartial spectator, the voice of conscience.

Title page of the first edition of the Wealth of Nations

The first edition of the Wealth of Nations was published in March 1776 by William Strahan and Thomas Cadell in the Strand, London. It quickly became a great success and established Adam Smith as a dominant figure in the discussion of political economy. This is one of five copies of the first edition held by the University of Glasgow.

Robert Burns’ Copy of the Wealth of Nations

This copy belonged to the poet, Robert Burns, and has his signature on the title page of each volume. Burns was an admirer of Smith, writing to Robert Graham in 1789, he said: ‘I could not have given any mere man credit for half the intelligence Mr Smith discovers in his book.'

Title page of the Essays on Philosophical Subjects

Smith’s final book was a collection of essays published posthumously in 1795 under the direction of his friends Joseph Black and James Hutton with a biographical note by Professor Dugald Stewart.

Educator

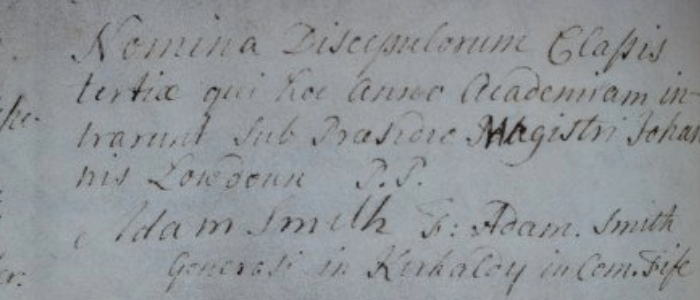

Matriculation Record

Adam Smith matriculated as a student at the University of Glasgow in 1737 at the age of 14. He remained as a student at Glasgow until 1740 studying under Francis Hutcheson and Robert Simson. His name is visible in the matriculation record in the University Archives.

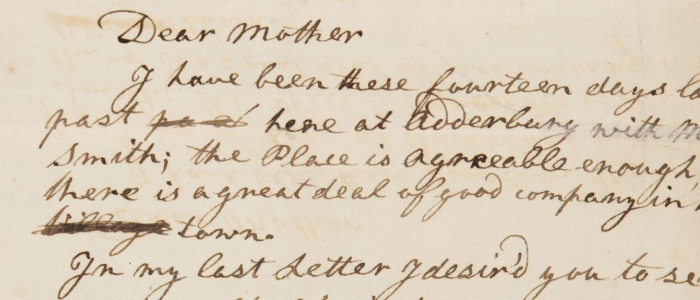

Letter to Mother from Adderbury

A letter from Adam Smith to his mother. Adderbury: 23 October, 1741. In this brief but congenial letter, an 18-year-old Smith writes to his mother asking her to ‘send me some stockings, the sooner you send ‘em the better’; he ends, ‘as you see, I have not very much to say’.

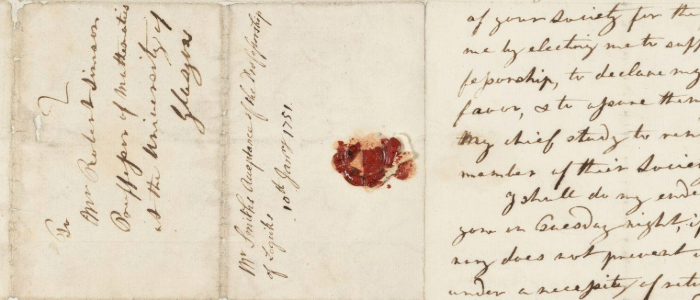

Letter of Appointment as Professor of Logic

Letter from Adam Smith to Robert Simson, Edinburgh: 10 January, 1751. Following his time at Oxford, Adam Smith began delivering public lectures in 1748 in Edinburgh under the patronage of Lord Kames. In 1751 he was appointed Professor of Logic at the University of Glasgow.

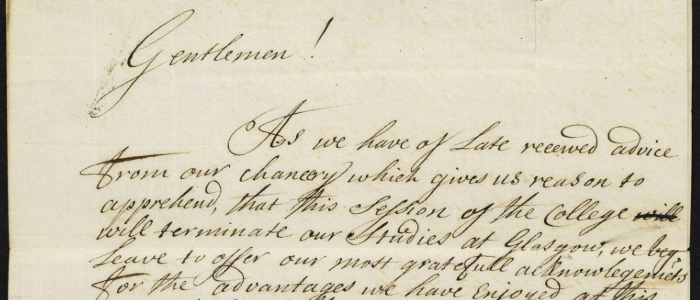

Smith’s Students

Smith was a popular professor, admired by the students who often went so far as to imitate his eccentric manners. Amongst his students at Glasgow were two young Russians, Ivan Tretiakov and Semen Desnitsky.

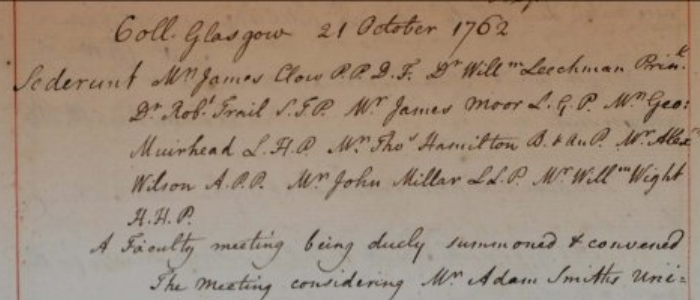

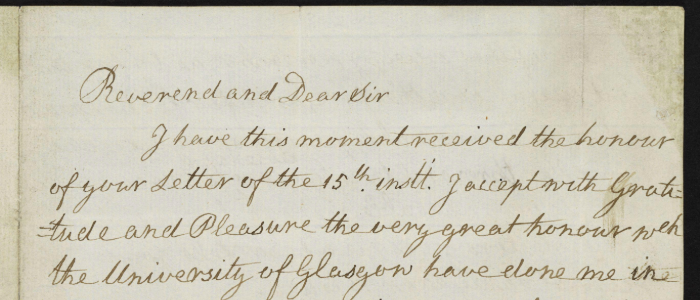

Honorary Degree

As was common at the time Adam Smith did not graduate from the University after his first period of study, but in 1762 the University decided to confer on him the Degree of Doctor of Laws, as recorded in the Dean of Faculty’s meeting minutes, 21st October 1762.

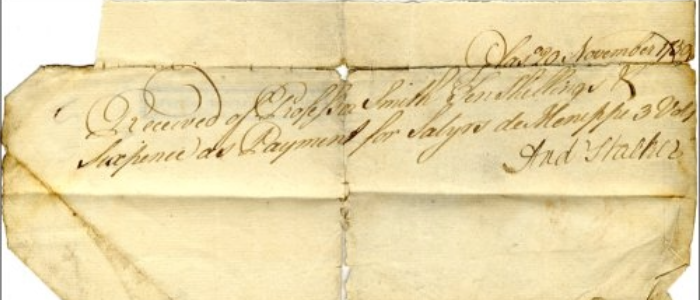

The University Library

Adam Smith was a voracious reader and recommended readings to his students. In this image, he secures a receipt on behalf of the University Library from Andrew Stalker for payment for Satyrs de Menippi (3 vols), 20th November 1759. Professors at Glasgow signed the Library borrowing book when they withdrew books, but they also signed to authorise student borrowing.

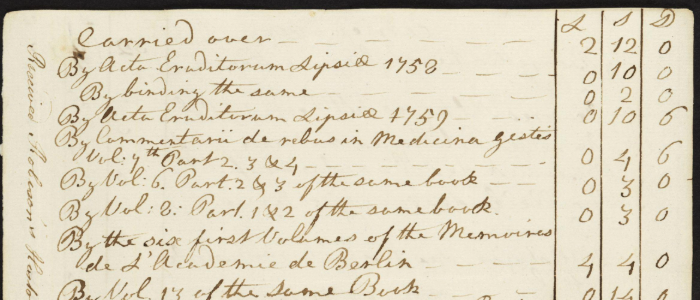

Quaestor Records

Adam Smith was intimately concerned with the University Library. He was Quaestor from 1758 until 1764, and in that capacity had the management of the Library funds. These accounts, written in Smith's own hand, show him recommending the most recently published histories of foreign countries and seven volumes of Diderot's Encyclopedie.

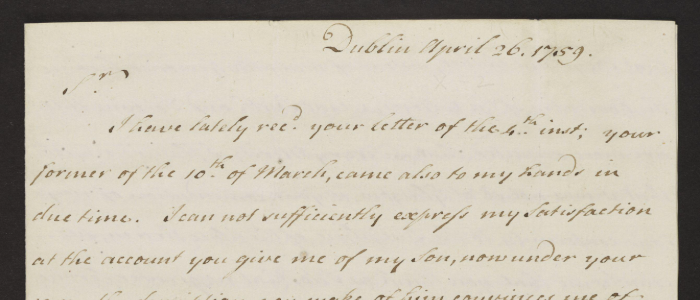

Letter from John Petty, 1st Earl of Shelburne (1706-1761) on care of his son

In his letter to Adam Smith, dated April 1759 Lord Shelburne expresses satisfaction with Smith's care and educational plan for his son, currently Smith's pupil. He emphasizes the importance of obedience, economy, and practical skills in his son's education, rejecting traditional academic institutions' focus on birth and fortune over merit.

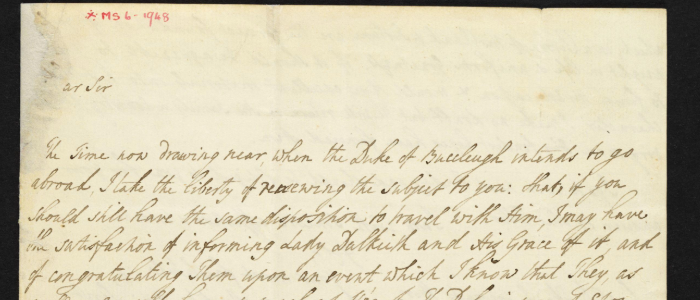

Letter from Charles Townshend on tour with the Duke of Buccleuch

The prominent politician Charles Townshend (1725-1767) writes to Adam Smith, discussing the upcoming travels of his stepson the Duke of Buccleuch and expressing a desire for Smith to accompany him as a mentor, an arrangement that both he and the Duke's family are eager to see happen. Townshend praises the Duke's progress in learning and character, emphasizing his potential and the positive impact Smith could have on his education and future.

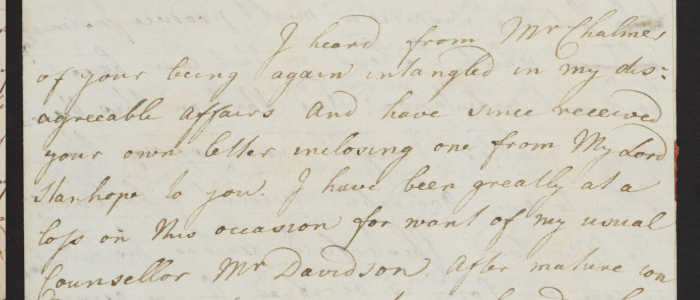

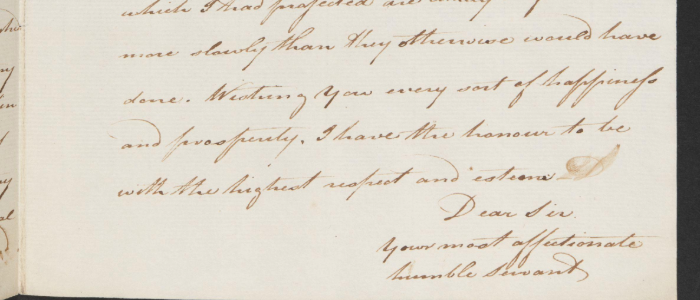

Letter from Adam Smith to Principal Davidson 16 Nov 1787

The prominent politician Charles Townshend (1725-1767) writes to Adam Smith, discussing the upcoming travels of his stepson the Duke of Buccleuch and expressing a desire for Smith to accompany him as a mentor. Smith would eventually leave the University to accompany the Duke on a tour to France in 1764.

Citizen

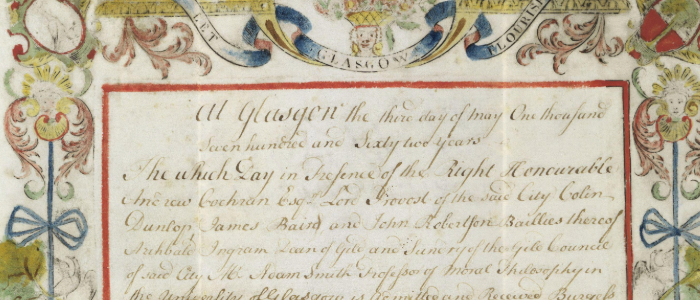

Adam Smith’s Glasgow Burgess Ticket

Original Burgess ticket, dated 3 May 1762, admitting Adam Smith as an honorary burgess of Glasgow. Engrossed on parchment and endorsed: 'Mr. Adam Smith His ticket of Glasgow, 1762.' Andrew Cochrane, Glasgow's greatest Provost, was the first to recognise Adam Smith's ability as an economist by securing his admission as an honorary burgess of Glasgow.

Letter from Adam Ferguson

Adam Ferguson (1723-1816) was a Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh and a friend and contemporary of Smith. Most famous for his An Essay on the History of Civil Society (1767), Ferguson and Smith enjoyed a fractious relationship and fell out over Smith’s suspicion that Ferguson had plagiarised his work.

Letter to Andreas Holt

Adam Smith was often approached for advice by politicians and administrators. This long letter from Adam Smith to Andreas Holt (1729-1784) is dated 26 October 1780. Holt was the Commissioner of the Danish Board of Trade and Economy and an influential politician.

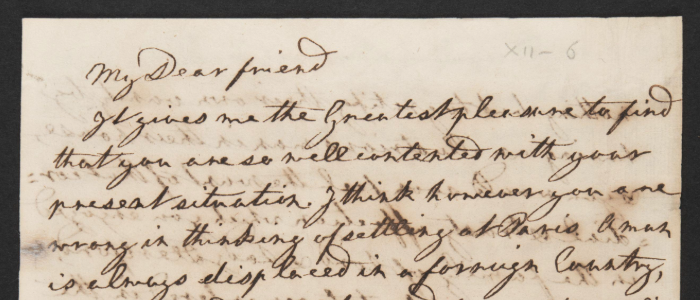

Letter to David Hume

1765 Letter from Adam Smith to his closest friend David Hume. Smith advises Hume against settling in Paris: Instead, Smith recommends London to Hume arguing that distrust of Scots will soon pass from fashion there.

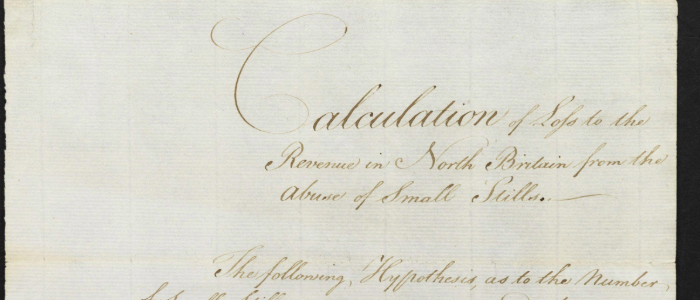

Loss to the Exchequer of small stills

Smith was appointed Commissioner of Customs for Scotland in 1778. He did not view this as an honorary office and instead devoted himself to his duties. In this note, Smith is attempting to assess the loss to the Scottish Exchequer of the bootleg distilling of whisky in small stills.

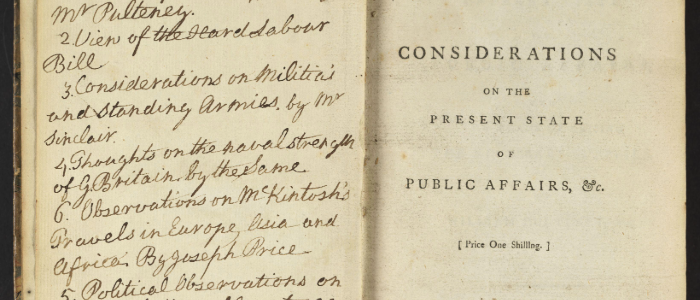

Adam Smith’s Pamphlets

Adam Smith kept up with current affairs and collected pamphlets on contemporary politics and economics. He often had these bound together in his private library. This image shows the list of handwritten contents for one of these volumes.

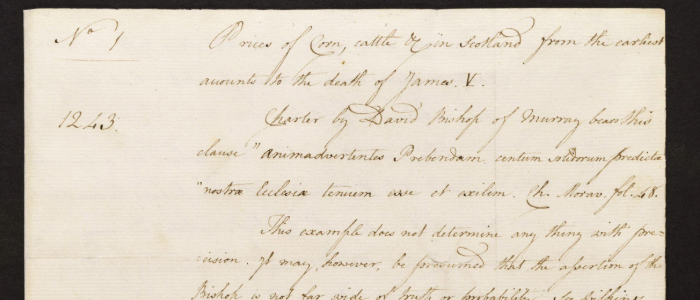

The historical price of Corn in Scotland

In the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith assembles and draws on extensive data on historical prices and production. He uses this to support his arguments. In these notes from Smith’s private collection, he collects data on the historical price of grain in Scotland.

John MacPherson to Adam Smith on the influence of his ideas

After publishing the Wealth of Nations Smith’s reputation on economic questions, he was frequently asked to advise on policy. In this letter from 28th October 1778, Sir John Macpherson (1745-1821) writes to Smith on various political discussions and developments, mentioning a successful speech influenced by Smith's ideas and a conversation with Lord North.

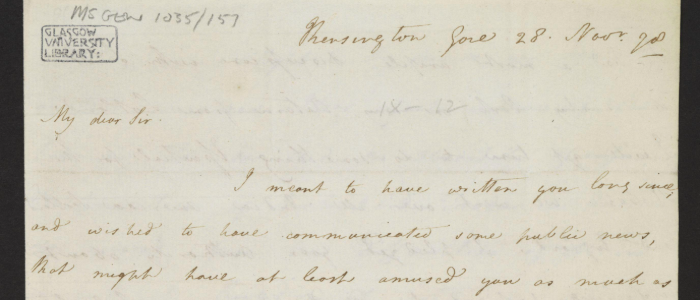

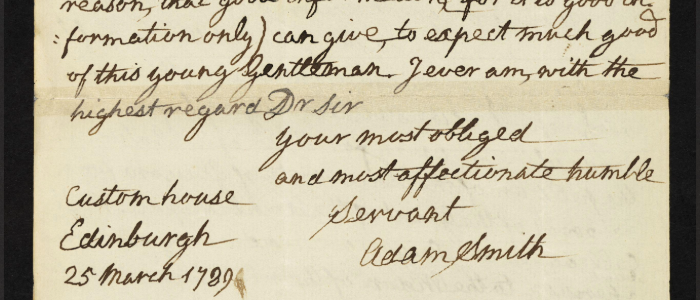

Letter to Henry Dundas

Letter from Adam Smith to Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, 25 March 1789, in which Adam Smith expresses satisfaction with a recent successful event. He then addresses administrative concerns related to the University of Glasgow. Smith also conveys gratitude from the Earl of Home for Dundas's correspondence.

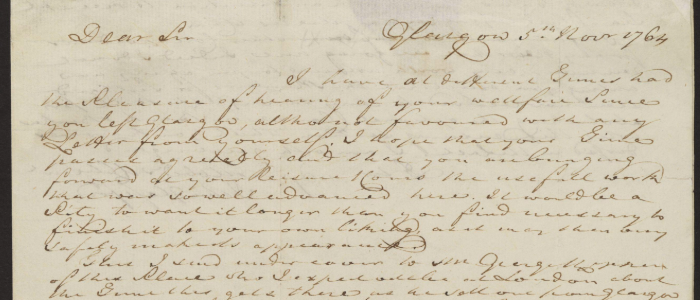

Letter from John Glassford to Adam Smith

John Glassford (1715-1783) was one of the most successful merchants in Glasgow. He and his fellow ‘Tobacco Lords’ dominated the trade in tobacco with Britain’s North American colonies. Smith maintained cordial personal relations with the Tobacco Lords despite his strenuous criticism of slavery, colonialism, and the trade monopolies from which they profited.