OBITUARY: Professor Simon Jeremy Thirgood ~ 6th December 1962 - 30th August 2009

The death of Simon Thirgood, at the age of just 46, marks the loss of one of the UK's leading ecologists and conservation biologists. Thirgood worked tirelessly to conduct and support ecological science that was useful, and to develop practical, scientifically informed environmental management strategies for a diverse range of conservation problems both in the UK, and overseas.

Thirgood was born in Liberia in 1962, and grew up in Vancouver, Canada, before moving to Scotland to study Zoology at the University of Aberdeen. Despite the distractions of the University's Lairig Club (the UK's most active mountaineering club) he graduated, and went on to complete a Ph.D. at the University of Southampton with Rory Putman on how fallow deer choose their mates. A post-doctoral position at Cambridge preceded his move to the Game Conservancy Trust, where with Steve Redpath he studied the controversial interactions of moorland management for red grouse and birds of prey. In Britain, there is a long-standing conflict of interest between estate managers who wish to run profitable grouse shooting, and the conservation of raptors that eat grouse. In their 1997 landmark publication Birds of Prey and Red Grouse, Thirgood and Redpath demonstrated that raptors, particularly hen harriers, could reduce grouse numbers below those required for economically viable grouse shooting. However, they went on to show that properly conducted and appropriately articulated science could persuade even those with most entrenched opinions to consider workable compromise solutions. The mix of science and policy, game-keepers and conservation biologists, theory and natural environments, was a perfect match to his character. Thirgood was particularly good at seeing the simple structure of complex-looking problems, and communicating the relevant science in straightforward ways to the people that mattered.

While at the Game Conservancy Trust, Thirgood met and married Karen Laurenson, a veterinary epidemiologist and together they went on to form a formidable and highly complementary scientific partnership. In 2003, they moved with their two young daughters to the Serengeti to work for the Frankfurt Zoological Society. This was an ideal environment for his mixture of practical science, policy development and implementation. Responsible for a wide-range of projects in Tanzania, Zambia and Ethiopia, Thirgood was quick to appreciate the important links between conservation and education in the developing world and worked constantly to advance African science. His efforts to promote Tanzanian conservation biology were recognized in a letter of commendation from the countries President.

Here, he ran a large research group, renewed his interests in Scottish upland ecology, further developed his interests in African conservation, and established an extraordinarily broad network of collaborations across the UK. He set out to develop and lead a science program infused with his values of pragmatism and policy relevance. Thirgood's unusual background enabled him to bring both more science to conservation, and more conservation to science - a rare and important perspective, and one that will live on with his legacy. The result was better science, and more effective conservation biology. Ultimately, he published more than 100 scientific papers, edited two books, and received honorary positions at the Universities of Glasgow and Aberdeen in recognition of the strong collaboratory links he developed with scientists at these institutions. He was appointed by the British Ecological Society to be senior Editor of the Journal of Applied Ecology, and worked with the Journal of African Ecology, and Wildlife Biology.

Thirgood had a keen eye for nonsense, and was often less than stoic (and very entertaining) when forced to endure windy presentations of science he regarded as indulgent. However, with his many collaborators he was superb and friendship was always central. His inputs were always positive and constructive, as he doggedly nudged the science to focus on the most useful and important questions, gently chiding those overly pre-occupied with a technical detail, and constantly injecting humour and encouragement into the process. He was a driven critic of the inexorable bureaucratization of science, and while irreverent about the political niceties of modern science, he was, at the same time, very effective in their practice. He was much amused by self-importance and prioritized his time to mentor younger scientists, with whom he was hugely popular. He supervised numerous doctoral students even though he worked in University environments only briefly.

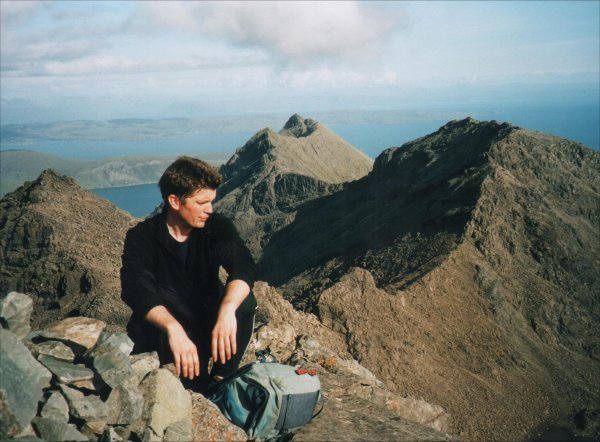

Thirgood lived and worked in some of the most spectacular ecosystems in the world, retaining always a great appreciation for the beauty of wild landscapes and the animals that live on them. He was an active outdoorsman, with a passion for climbing, particularly the rather masochistic form often practiced in Scotland. The history and traditions of Scottish mountaineering ran deep in him. There were few Munroes he didn't know well and he joyfully imparted his enthusiasm and experience to others. Later, the ravages of middle-age led him to more tranquil pursuits including canoeing and walking. Ultimately though, Thirgood was a family man, a loving husband, and wonderful father to his daughters Pippa and Katie. The family homes he and Karen created, whether tucked away on the banks of the Dee or nestled into the rocky outcrops of the Serengeti, were bastions for friends and colleagues alike, and legendary for the warmth and generosity of their entertaining hospitality.

Following the award of a large European grant to study sustainable hunting in Africa and Europe he embarked on a hectic schedule of overseas travel. The week he died he was visiting conservation researchers in Ethiopia to set up a project, funded by the UK Darwin initiative, to link monitoring of biodiversity by local communities with more scientific approaches. He was killed when a building in which he was staying collapsed during a sudden storm. His life was full of energy, humour and friendship. His death is a sudden and huge blow to UK and international conservation at a time when his unusual combination of skills is so desperately needed, and a terrible loss to the family he adored, and who can be so proud of him.