Extreme Imagination

Exhibition Essays

The investigators on the Eye's Mind Project were fortunate to hear from many thousands of people with extreme imagery. To our surprise, these included a good number of aphantasic artists. This provided the impetus for our exhibition – we wondered what if anything is distinctive about the work of those with extreme imagery? How does an artist with aphantasia work? Can one spot the hyperphantasic mind in action?

Each member of our project team has contributed an essay to this catalogue, providing a truly interdisciplinary set of insights into imagery – from a philosopher, an artist, an art historian, a literary historian, a neurologist and a neuroscientist. Artists' statements about their own work can be found accompanying the images in the online exhibition – and you can also watch the Artist Interviews and watch their contributions to our Conference.

Curators’ Introduction by Susan Aldworth and Matthew MacKisack

To cite this: Aldworth, S. and MacKisack, M. (2018) 'Curators' Introduction', in S. Aldworth and M. MacKisack (eds.) Extreme Imagination: Inside the Eye's Mind, London: University of Exeter, pp. i-v

This exhibition invites us to consider the role of mental imagery in making art. As far as we are aware, this is the first exhibition to do so – perhaps because the centrality of mental imagery to art-making has previously been assumed. This itself may be because the popular model of how artists work is something of a Romantic stereotype: that they are realising a ‘vision’.

What the artists – and architects, and writers, and milliners – included in the exhibition show, however, is that having mental imagery is not a prerequisite for making art or even being creative. Collected from responses to Adam Zeman’s initial identification of ‘aphantasia’ and then an open call for artworks by individuals with aphantasia and its opposite, ‘hyperphantasia’, the exhibiting artists are a necessarily diverse bunch, from criticallyrecognised professional to intuitively expressive amateur.

This is because they are bonded by a neuro-psychological trait, above anything else; as they work with their personal lack or abundance of internal imagery, they demonstrate the diversity of means by which artworks can come into being. For the aphantasics, one of these means is to ‘copy’ directly from a source, be it an object in front of them or a group of photographs.

Daan Tweehuysen paints in a ‘photorealistic’ style, that demands a high level of attention to detail. It seems that lacking mental imagery, as Tweehuysen does, might offer a positive advantage – one can attend directly to what one is trying to represent, perceive what is ‘really’ there, without the imagination suggesting what might be.

The contents of Stephanie Brown’s surreal and evocative images are drawn entirely from photographs. No part of it, or indeed how the painting itself will ultimately look, is imagined beforehand. Instead, with a scene from a story as the initial prompt, she will methodically work out what the piece requires – a process of deduction and planning, rather than visualisation.

While the pictures they make are stylistically opposed, both Hillah Nevo and Elina Cerla emphasize, in lieu of a sense of what things look like, the importance of a spatial sense (which, interestingly, might correspond to a recognised division in the brain’s visual information processing: one ‘stream’ subserves predominantly object vision (see e.g. Haxby et al 1991), the other subserves primarily spatial vision and action (see e.g. Goodale et al 2004)).

Several other aphantasic artists report ‘working blind’: rather than depending on an immediate reference, they let the image emerge from the picture surface. Imagining is, in a sense, subsumed into the physical act of making the marks; the surface of the canvas substitutes for the mind’s eye. This is strikingly the case with Michael Chance, who paints elaborate figurative scenes without physical or mental reference material – the time-lapse video included the exhibition gives a fascinating glimpse of his working process. Sheri Bakes speaks in similar terms of her semi-abstract clouds of colour: they “have become the picture inside that I can’t see”.

Susan Baquie’s and Andrew Bracey’s related strategy is to start with some pre-existing material. They thus have, from the outset, something ‘out there’ to work with: Baquie collages, altering and combining paper, while Bracey digitally manipulates images of old master paintings, slowly erasing them, until they conform to his own interior imagelessness.

For the milliner Claire Strickland and architect Trevor Keetley, perceiving – rather than imagining – is integral to the design process: Keetley uses explanatory sketches to aid his own understanding as much as convey ideas to others; Strickland often begins by trying out arrangements on her own head, in front of the mirror. Those working with language are subject to similar assumptions about the role of imagery. We are frequently told that creative writing begins not with words but with a ‘vision’ which the writer then describes. “Somewhere in the blood you have a play, and you wait until it passes behind the eyes” was Arthur Miller’s version of this view (Miller, 1966).

Inspiration may well take this form for those with imagery, but the ‘mind blind’ must develop other strategies. Elisabeth Tova Bailey, for example, works with “experience, concept, and emotion”, rather than imagery. Dustin Grinnel’s novels, similarly, are made from ‘concepts’ – knowledge about characters’ intentions, and so forth – that he forms into a logical plot.

And when it comes to scenic description, he will use photographic references or borrow ‘useful’ descriptive language from other texts. Rather than plan what the film will look like, screenwriter Alejandro Hernandez Murillo’s storyboards convey just enough information to differentiate characters and note action. Indeed, there’s a sense in which aphantasia’s challenges might actually advance narrative technique: as the children’s author Benjamin Hendy points out, aphantasia makes him focus on “what happened … not where”.

If such are the strategies employed by those who do not experience mental imagery, what of those at the other end of the range of reported imagery vividness, the ‘hyperphantasics’? It is worth remembering how remarkable hyperphantasia is for the individual: it means, as the commonly-used VVIQ test has it, that their mental imagery is ‘as vivid as real seeing’. The hyperphantasic can inspect their mental imagery in a way that others might examine a photograph held in their hands. This ability leads to particular ways of working.

Melissa English Campbell plans her woven artworks in her mind’s eye, mentally designing the weave structure to the last detail before even starting the physical piece. Others, such as Megan Eckman, Claire Dudeny, Kirsten Baron, and Elvenia Ruusu, might have less control over their imagery – occurring to them spontaneously, in dreams or pareidolia – but are then able to depict or ‘externalise’ what they have experienced. For the work included in this exhibition, Geraldine van Heemstra painted the colours and shapes she experiences in response to music: a synaesthetic form of hyperphantasia (for which the art-historical precedent would be Wassily Kandinsky, who, listening to Wagner, “saw all my colours in spirit, before my eyes … [w]ild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me”) (Kandinsky, 1982, p. 341).

It is not only working methods which are informed by aphantasia and hyperphantasia; for several artists in the exhibition, the discovery of their own ‘condition’ has had almost existential ramifications. For Dominic Mason, it explained difficulties he had had with activities that are integral to being a contemporary entrepreneurial conceptual artist, such as proposing projects and communicating ideas; his work is now focused on analysing what it means to be a ‘mind-blind’ artist.

Like several others in the exhibition, Isabel Nolan always had to physically make the work “to discover what it might do” (Nolan, 2018). But learning that she was aphantasic also forced her to rethink how she interprets her art-historical forebearers: is it her aphantasia, she wonders in a recent performance lecture, that makes her perceive the Stone Age Löwenmensch sculpture as a mundane experiment in form, rather than, as is often attributed to it, “the spirit realm [made] into tangible reality ’”? (ibid.) Is it not possible that somebody might fashion it to ascertain what the offspring of a lion and a human would look like – for the same reason, that is, that she, as aphantasic, makes things?

The lack of conscious imagery, then, has multiple implications for artistic practice – but none, as the works collected here demonstrate, for the creativity or imaginativeness of the artist. It seems that aphantasia instead can have a more ‘holistic’ affect, influencing one’s self-perception, as much as the decisions one makes about how to work and what to do. For example, having no ‘plan’ as such, you just start making marks and see where they lead, or you make things out of other pre-existing things; to avoid having to ‘invent’, you make copies.

Of course, people without aphantasia do all these things anyway. And one couldn’t know which of the artists were hyperphantasic and which were aphantasic just by looking at their work, or even, indeed, if there was anything unusual about their inner lives. But that is what Extreme Imagination hints at: the diversity of the hidden routes to creation.

References

Goodale M.A., Westwood D.A., Milner A.D. (2004). Two distinct modes of control for object-directed action. Prog Brain Res 144:131–144

Haxby J.V., Grady C.L., Horwitz B., Ungerleider L.G., Mishkin M., Carson R.E., Rapoport S.I. (1991). Dissociation of object and spatial visual processing pathways in human extrastriate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88(5):1621–1625

Kandinsky V. (1913): ‘Reminiscences’ in Lindsay, K., Vergo, P. (eds. and trans.) (1982) Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art. London: Faber & Faber

Miller, A. (1966). ‘The Art of Theatre no 2’, The Paris Review, 38

Nolan, I. (2018). Presentation. Grazer Kunstverein

Phantasia: the (re)discovery and exploration of imagery extremes, by Adam Zeman

To cite this: Zeman, A. (2018) 'Phantasia: the (re)discovery and exploration of imagery extremes', in S. Aldworth and M. MacKisack (eds.) Extreme Imagination: Inside the Eye's Mind, London: University of Exeter, pp. 6-13

In 2003 the canny Professor of the neurology depart- ment in Edinburgh, where I then worked, handed me an unusual referral letter: “Adam, I think this is your kind of thing” . It requested that we assess a man in his mid-sixties, MX, who had undergone a procedure to treat the narrowed arteries in his heart. During his recovery he noticed a subtle but – for this highly visual and observant man – striking change in his experience: he could no longer visualise: as the referral letter put it, “following on from the procedure … he is now unable to imagine anything” . And so it proved: MX, a surveyor by profession, had always enjoyed imagining the faces of friends and relations, the appearance of favourite locations, the look of things to come. After his angioplasty, he was unable to bring a single image to mind. This change was pervasive: it affected his dreams, which continued, but in an a-visual form; he loved novels, but now, when he read a fictional description, no visual scene unfolded at the fringe of consciousness.

We used functional brain imaging (fMRI) to show that while looking at faces gave rise to entirely normal activation in MX’s brain, imagining them failed to activate the visual regions which are thought to give imagery its visual feel. We described his ‘blind imagination’ in a scientific paper (Zeman et al., 2010), and I thought the job was done. But events then took an unexpected turn. Carl Zimmer, a respected American science writer, spotted the tale of MX and described it in his column in Discover, a popular US science magazine.

Over the next few years I received a series of emails from readers who had recognised themselves in Zimmer’s account of ‘blind imagination’, but with a crucial difference: they had never been able to visualise. They usually discovered this in their teens or twenties, and their epiphany was often the realisation that others could see ‘in the mind’s eye’ rather than that they could not, as this latter fact was already well known to them. They were delighted that someone was taking an interest in a quirk of their nature that was, they felt, widely significant for their lives, but hard to explain to others.

This phenomenon, the lifelong lack of the ability to visualise, had never been fully described and lacked a convenient name. I consulted with a classicist friend, David Mitchell, who advised we borrow the term of one of the Greek fathers of philosophy, Aristotle, for the mind’s eye – ‘phantasia’ – prefixing it with an ‘a’, to denote absence: so ‘aphantasia’ was born (Zeman, Dewar, & Della Sala, 2015).

The term and concept attracted huge interest, which continues, with publicity around the world, including notable coverage by James Gallagher on the BBC and the entrepreneur, Blake Ross, whose Facebook post on the topic went viral. Almost three years later we have heard from around 11,000 people with ‘extreme imagery’, most with aphantasia, but many, also, with its counterpart at the opposite end of the vividness spectrum, ‘hyperphantasia’, who experience imagery so vivid that it rivals ‘real seeing’. Is aphantasia really novel? The term is new, but the phenomenon is not.

My collaborator, Dr Michaela Dewar pointed me to the work of Sir Francis Galton, a pioneer of measurement in psychology, who had recognised in an article published in 1880 that some people lacked the ‘power of visualisation’ (Galton, 1880). He suspected that this was especially common among ‘men of science’. Strangely, no one had followed up this lead in the last century, with the sole exception of an American psychologist, Bill Faw. Faw is himself aphantasic.

He surveyed his students, estimating that 2% of the population lack imagery, a figure roughly in keeping with our own results (Faw, 2009). Two other, separate, lines of research hinted at intriguing associations with imagery vividness: researchers studying ‘prosopagnosia’, a usually lifelong and sometimes inherited difficulty in recognising faces, noticed that their participants tended to report fainter than usual imagery (Gruter, Gruter, Bell, & Carbon, 2009); in contrast, students of ‘synaesthesia’, the ‘merging of the senses’ that enables some people, for example, to taste colours, had reported more vivid than usual imagery among synaesthetes (Barnett & Newell, 2008).

The bonanza of information from our 11,000 contacts has opened a window on the experience of people with ‘extreme imagery’. Aphantasia does indeed appear to be associated with face recognition difficulty in around one-third of our participants, an intriguing association, as the basis for the link between the perceptual ability to recognise faces and the imaginative capacity to visualise things in general is not immediately clear.

Another, overlapping, third of participants report a reduced ability to recollect memorable events from their past lives. This is a more intuitive connection, as, for most of us, visual imagery makes a big contribution to the ‘remembrance of things past’. But people with aphantasia often describe positive associations alongside these apparent deficits, with many of our participants reporting strengths in abstract and mathematical forms of thought. Feeling may benefit too: people with aphantasia describe themselves as being more ‘present’ than their visually imaginative friends and relations, with a greater ability to ‘move on’ when the need arises.

There are some variations within the group, suggesting that aphantasia is not a single ‘thing’: about half of our participants report visual dreams, which give them an insight into what it is like to visualise – pointing to an important distinction between wakeful and dreaming imagery – but half do not; around half report that imagery is absent in all modalities – they have no mind’s ear, for example – while the remainder experience imagery in other senses.

Hyperphantasia seems to be the mirror image of aphantasia, with normal or strong face recognition ability and autobiographical memory; a tendency to work in creative professions; an increased chance of synaesthesia; a liability to be waylaid by imagined worlds; a risk, at times, of confusing real with imagined events. Participants in both categories – a- and hyper-phantasia – have told us that their close relatives share their flavour of extreme imagery more often than would be expected by chance, hinting at, though not proving, a genetic influence.

At the outset of this work, while there was evidently much to learn, I took one thing for granted – people with aphantasia would not be much attracted to the visual arts. Fifty or so fascinating messages from aphantasic artists – and authors and sculptors and architects – later, I accepted that I had been wrong. Some mistakes are illuminating: my surprise at this unexpected twist, shared by the other members of our Eye’s Mind team, encouraged us to lay plans for the current exhibition of work by artists with ‘extreme imagination’.

My guess that visual artists would generally incline towards the vivid end of the spectrum was probably correct, but the aphantasic artists who made contact share a love of the visual world. They use their art as a way of capturing and celebrating appearances that are unavailable to their mind’s eye. For some it is important to be able to work from life; for others the canvas or page provides a medium for images that emerge as they work their work, in a sense, provides their mind’s eye. Aphantasic authors are able to conjure imagery in their readers that they lack in their own lives.

Aphantasic architects create satisfying spaces that they cannot visually anticipate. We were intrigued. Aphantasia is clearly no bar to a highly creative existence. This gave me pause for thought, on two counts in particular: concerning, first, representation, and, second, imagination. Our ability to represent things in their absence – or ‘displaced reference’ – is crucial to our mental lives, both to our inner experience, as when we recollect the past and daydream about the future, and to our social exchanges, when we converse.

Aristotle had written that “the soul never thinks without a phantasma”; the medieval philosopher, St Thomas Aquinas, had echoed him: “…when one tries to understand something, one forms certain phantasms for oneself by way of examples…”; David Hume, the Scots 18th century empiricist, reported that “when I shut my eyes and think of my study, the ideas I form are exact representations of the impression I felt when I was in my study” (see MacKisack et al., 2016 for further historical examples) – yet, the thousands of individuals contacting us with aphantasia seemed perfectly well able to represent the world in its absence without using visual imagery at all.

They gave eloquent descriptions of alternative modes of a-visual, and even a-sensory, forms of reference: “the shape of an apple if you felt it in your hands in the dark” ; “like painting with jet-black paint on a jet-black canvas, you can see it in the movement” ; “thinking only in radio” ; “being the object” ; “I excel in mental rotation – I can’t begin to describe how”. The phenomenon of aphantasia underlines the huge variations in human experience – and the corresponding danger of assuming that one’s own experience is universal, or even typical. Fascinating differences between our inner lives can very easily escape attention (Gruter & Carbon, 2010).

While aphantasia points to the variety of ways in which we can represent the world, it also highlights the complexity of the ‘imagination’. Many of our contacts were understandably indignant at the suggestion – which we had not intended – that they were ‘unimaginative’. For one thing, imagination can operate creatively quite independently of the visual domain – in language, or in music for example. For another, there is far more to imagination in any domain that the mere capacity to represent things in their absence.

As Susan Aldworth, the curator of our exhibition, discovered when she began to ask fellow artists about their understanding of the visual imagination, it is “a fluid process… a way of finding solutions to problems… the ultimate instrument for play, art, escape… a way of life”. The concepts of a- and hyper-phantasia have proved unexpectedly fruitful. Our description of these imagery extremes has attracted interest from teachers, therapists, psychologists and neuroscientists; inspired a novel (Miller, 2017) and a memoir (Kendle, 2017); excited philosophers and film-makers. Yet there is much work to do. Most of the associations I have outlined depend on ‘first-person’ testimony – surely the best, indeed the only, place to begin, but by no means the end of the story.

There are legitimate questions about the accuracy of our introspection – whether directed at the vividness of our visual images or the detail and fidelity of memory – and about the effects of these imagery extremes on our mental lives. There is no substitute for measurement. We are in the process of ‘triangulating’ the first person reports that have reached us with objective measures – of cognitive processes, like memory and of personality; of brain structure and function; and, more tentatively at this stage, of genetic markers that may eventually help us to understand the biological basis of visualisation.

While the majority of our participants describe lifelong or ‘congenital’ aphantasia, a minority, like my original patient, MX, describe the loss of a prior ability to visualise: some- times as a result of brain damage, sometimes as a result of psychological disturbance. We are beginning to study these contributors too, using the same mixture of first-person and third-person approaches (and will keep our website – http://medicine.exeter. ac.uk/research/neuroscience/theeyesmind/ – updated with all our results).

The opportunity to explore these imagery extremes has been and continues to be extremely exciting – linking a fundamental aspect of our inner lives with forms of artistic expression, patterns of cognitive performance and details of structure and function in the brain. This work could never have happened without the internet, which has allowed large numbers of interested participants to get in touch easily; without the techniques of modern neuroscience, like functional MRI scanning, that have given researchers the confidence to hunt for objective correlates of subtle features of experience; and, of course, without the many people who have made contact and generously shared their experience with us.

I keep some particularly poignant messages pinned to my office board. One life-long aphantasic participant pointed me to Al Pacino’s evocative line in Scent of a Woman: “I’m in the dark here” . Another pointed to a way through the darkness: “I am learning how to love without images”.

References

Barnett, K. J., & Newell, F. N. (2008). Synaesthesia is associated with enhanced, self-rated visual imagery. Conscious. Cogn, 17(3), 1032–1039

Faw, Bill (2009). Conflicting intuitions may be based on differing abilities – evidence from mental imaging research. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 16, 45–68

Galton, F. (1880). Statistics of mental imagery. Mind, 5, 301–318

Gruter, T., & Carbon, C. C. (2010). Neuroscience. Escaping attention. Science, 328(5977), 435–436

Gruter, T., Gruter, M., Bell, V., & Carbon, C. C. (2009). Visual mental imagery in congenital prosopagnosia. Neurosci. Lett, 453(3), 135–140

Kendle, A. (2017). Aphantasia: experiences, perceptions and insights. Stoke on Trent, UK Bennion Kearny Ltd.

MacKisack, M., Aldworth, S., Macpherson, F., Onians, J., Winlove, C., & Zeman, A. (2016). On Picturing a Candle: The Prehistory of Imagery Science. Front Psychol, 7, 515

Miller, L. (2017). All Things New. LA, USA: Three Saints Press

Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della, S. S. (2015). Lives without imagery – Congenital aphantasia. Cortex, 73, 378–380

Zeman, A. Z., Della Sala, S., Torrens, L. A., Gountouna, V. E., McGonigle, D. J., & Logie, R. H. (2010). Loss of imagery phenomenology with intact visuo-spatial task performance: a case of ‘blind imagination’. Neuropsychologia, 48(1), 145–155

What Is It Like to Have Visual Imagery? by Fiona Macpherson

To cite this: Macpherson, F. (2018) 'What Is It Like to Have Visual Imagery?', in S. Aldworth and M. MacKisack (eds.) Extreme Imagination: Inside the Eye's Mind, London: University of Exeter, pp. 21-29.

How does visual imagination differ from visual perceptual experience? And how should we describe experiences of visual imagery? Moreover how can people who have visual imagery convey what it is like to have it to those who have never had it – congenital aphantisics? These are difficult questions. The latter is particularly difficult if we believe the claim, frequently made by philosophers, that if you have never had an experience of something, then you cannot know what it is like to experience it.

For example, if you have never experienced colour, then you cannot know what it is like to experience colour. What differences have been proposed between visual perceptual experience and visual imagination? Philosophers have proposed a few. It has been noted that visual imagination is typically voluntary in a way that perception is typically not. It has been suggested that visual experience conveys to one the existence of certain objects and properties, while visual imagination does not. Imagination only conveys to one what could be the case.

However, even if these are true, they fail to convey what it is like to have an experience like that. David Hume, the famous Scottish Philosopher, said that visual imagery is less ‘vivid’ and ‘lively’ than visual experience. While to many people these words strike a chord, it is not obvious exactly what they mean, and what qualities they identify, for perceptual experience itself can be more or less vivid or lively – compare a visual experience of a bright carnival scene and one of a London fog – just as visual imaginative experience can be.

So use of these terms seems rather metaphorical. Moreover, it is not clear that knowing these facts about the difference between visual perceptual experience and visual imagination – if indeed they are facts – helps one to know exactly what it is like to have visual imagination if one has not had that experience. However, fortunately, David Hume pointed out a counter example to the thesis that if you have never had an experience, then you cannot know what it is like to experience it.

The case is one in which you have not experienced something, but you have experienced other things that are very similar, which allows you to know what it would be like to experience that something in question. For example, suppose that you have not seen a particular shade of blue. You might come to know what it would be like to experience the ‘missing shade of blue’ if you had seen very similar shades more or less bright, more or less saturated, and more or less bluish.

Can we use this methodology – identifying similar experiences to those of visual imagery – to convey to congenital aphantasics what it is like to have visual imagery? In this essay I attempt to do so. Some aphantasics have visual dreams. Is that what it is like to have visual imagery? In my own experience, some dreams are like imagery to the extent that on reflection when one has woken, they seemed to be somewhat indeterminate.

However, certainly at the time I was having them, I took them to be perceptual experience. In any case, some aphantasics do not dream. Can we identify experiences that they can have that are quite like having visual imagery? Four examples spring to mind: modal completion, neon colour spreading, amodal completion, and afterimages. What is common to them all is that while you experience them you can also appreciate that what you seem to experience isn’t really there, as is the case with experiences of visual imagery.

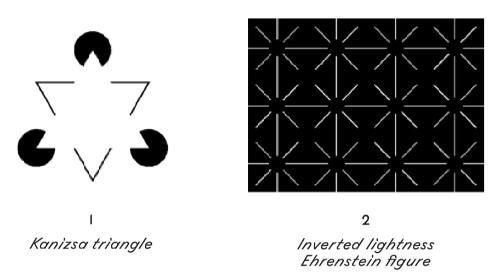

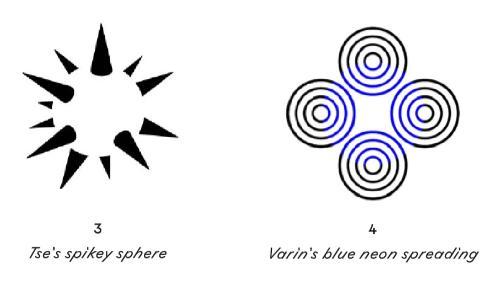

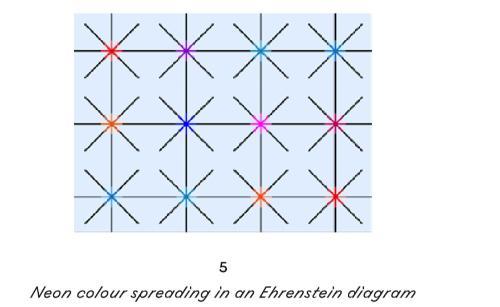

In modal completion you have a visual experience as of an object in virtue of experiencing edges that appear to be created by a luminance, colour or texture boundary. On reflection, you can tell that there is no such boundary and there is not a difference in luminance, colour or texture where there appears to be one; but, nonetheless, that is what you experience. For example, in the Kanizsa triangle figure 1 there appears to be a triangle that is lighter in colour than the background pointing upwards. If you pay close attention to the figure you can recognise that in fact there is no difference in lightness between that triangle and the background. The luminance contour is an illusion.

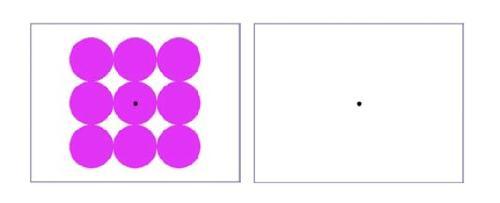

A similar effect can be seen in the black disks in the Inverted lightness Ehrenstein figure 2, and Tse’s spikey sphere 3 provides a nice 3-D example. Another comparible effect occurs in the two examples of neon colour spreading 4, 5 in which you experience different coloured disks that you can also appreciate are illusory disks – the colour only really forms the lines of the figures, and the disks are not really there.

In all of these examples, when you realise that the shape that you experiences is not really there, you have an experience that is somewhat like having visual imagery – an experience in which in some sense you visually experience something but, in another, you realise that it isn’t in the world before you. Nonetheless, despite sharing this one feature with imagistic experiences, these examples are far more like perceptual experience than imagery in all other respects.

A better example of a perceptual experience that is somewhat like visual imagery comes in the form of amodal completion. Amodal completion occurs when part of an object is experienced as occluded and is reported as having a particular shape. It contrasts with modal completion as the occluded portion of the object is not experienced as being defined by a colour, lightness or texture boundary. One example is the downward pointing triangle in the Kanizsa triangle figure. There appears to be a whole downward pointing triangle occluded by the upward pointing triangle that is defined by the illusory lightness contours. Yet, in the figure, strictly speaking, there is no downward-facing triangle. There are simply three black angles that, if connected, would form a triangle. Unlike the upward pointing modally completed triangle, the downward pointing triangle’s sides do not appear within our experience in virtue of a colour or lightness boundary. Yet, still, in some sense they seem present in our experience. In other words, the downward pointing triangle is amodally completed. The horizontal and vertical white lines in the Inverted lightness Ehrenstein figure are also usually perceived as amodally completed – they appear to continue behind the discs – but they are not experienced in virtue of an experience of an apparent luminance or colour boundary.

Likewise, the apparently occluded footballer’s long arm provides an amusing example of amodal completion. Like modal completion, amodal completion is also somewhat like experiences of visual imagery. In some sense you are clearly not seeing an object or part of object, yet in another one has a clear visual sense of it’s being there. I would say that modal completion and dreams overshoot the target of being like visual imagery by being too vivid and lively, while modal completion undershoots by being less vivid and lively than visual imagery – at least my visual imagery. But amodal completion is perhaps the most similar experience that I can identify to visual imagery.

One way in which visual imagery can – but needn’t – differ from amodal completion is that whereas in amodal completion there is a sense of the amodally competed part of the object being in front of one now, that needn’t be the case with imagery. For example, one can visually imagine something taking place yesterday and one can visually imagine something taking place on the other side of the world where one can’t see it. Of course this needn’t be the case. One can imagine something happening here and in the space visible to one, as I do now when I imagine a little green man sitting on the computer that I see in front of me.

A final case I’d like to consider is having an after- image. When one does so, one often realises that what one is experiencing isn’t really present before one. Stare at the picture of the magenta circles and keep your eyes focused on the central black spot for about one minute. Then stare at the black dot in the empty frame beside them. Blink your eyes a couple of times if required. You should see a green afterimage of a group of circles.

Afterimages usually seem to move as your eyes move (although the green circles tend not to as due to the fixation dot and the surrounding black border) and you can often tell, even when not expecting to view an afterimage, that it is an afterimage by this feature of the apparent object. Likewise, one can have a photo-realistic afterimage by focusing your eyes on the dot on the bridge of the nose of the strangely coloured face for around one minute and then looking at a white surface, like a wall or piece of paper – again perhaps blinking one’s eyes a few times.

Afterimage, Dimitri Parant, 2011 © CC BY-SA 2.0

What it is like to see these afterimages is not exactly like what it is like to visually imagine green circles or Amy Winehouse’s face – like modal completion they seem more vivid and lively than visual imagination – but it is certainly more like imagery than a standard visual perceptual experience of those things. Can we identify other experiences that are like imagery? Can we come up with better descriptions of how visual imagery and visual perceptual experience differ?

These are questions that I will continue to consider. However, I hope that the experiences discussed in this essay help those who have never experienced visual imagery to better understand what it is like to have it. In closing, I would like to discuss a feature of aphantasia that people who lack it often seem surprised by. People with aphantasia can do many tasks that people who have visual imagery seem to do in virtue of having that visual imagery. People who can visualise can be surprised that aphantasics can do these tasks when they don’t have the imagery that apparently allows those who have such imagery to do them.

For example, people who can visually imagine might wonder how someone can know the number of windows in their house when they can’t visually imagine walking round their house and counting them. How can they know what colour their partner’s hair is if they can’t form a visual image of their partner? (Indeed, switching modalities from vision to hearing, there is a long history in thinking that one cannot think unless one has auditory imagery of a voice in one’s head.)

However, the surprise of those who have visual imagery comes from, somewhat ironically I think, a lack of (non-perceptual) imagination, for there are many questions that those with visual imagery know the answer to without having to form visual images. If you have visual imagination, think to yourself how you know what the sum of two plus two is. It is likely that you do not need to visually imagine two objects, or imagine the numerals, in order to come up with the answer – you just know it.

Or think how you know what your partner’s name is. You don’t need to visually imagine your partner or the letters that make up their name to know – you just know. The answer just pops into your head. This, according to the reports I have read and heard from aphantasics, is what it is like for them when they come up with answers to questions that those with visual imagery would answer by consulting their visual imagery. Thus it is perhaps not such a surprising phenomenon as some would make out.

Importantly, it also raises the fascinating question of whether the visual imagery of those who have it actually plays the role of allowing them to come to know the answer to certain questions, which those people believe it does, or whether, counterintuitively, it is a mere accompaniment to their so doing. What aphantasia and other examples show us is that there are a variety of fascinating mental differences between people, which confer different abilities to them. Studying these allows us to find out about each other and ourselves, and to gain a better understand of our minds and the nature and role of different forms of consciousness.

References

Ehrenstein, W. (1941). ‘Über Abwandlungen der L. Hermannschen Helligkeitserscheinung’, Zeitschrift für Psychologie 150 pp. 83–91

Kanizsa, G. (1955). ‘Margini quasi-percettivi in campi con stimolazione omogenea’, Rivista di Psicologia, 49 (1) pp. 7–30

Tse, P. (1998). ‘Illusory volumes from conformation’, Perception, 27 (8): 977–994

Varin, D. (1971). ‘Fenomeni di contrasto e diffusione cromatica nell’organizzazione spaziale del campo percettivo’, Rivista di Psicologia 65, pp. 101–128

Harvesting the Imagination, by Susan Aldworth

To cite this: Aldworth, S. (2018) 'Harvesting the Imagination', in S. Aldworth and M. MacKisack (eds.) Extreme Imagination: Inside the Eye's Mind, London: University of Exeter, pp. 30-35

Professor Adam Zeman asked me in 2014 to be part of the Eye’s Mind project. I am a visual artist with a background in philosophy and a long-standing interest in the workings of the human mind, in particular consciousness and our sense of self.

Susan Aldworth, Heartbeat 1, 2010. Lenticular print. Reproduced with permission of the artist and TAG Fine Arts

For this project, I have explored what ‘visual imagination’ means to individual artists (both contemporary and historical) and what role it might play in the way they make their work. At the same time it was surprising to find that a significant number of people who presented with aphantasia and hyper- phantasia are visual artists.

Reading the artist statements of participants in the Extreme Imagination exhibition alongside the descriptions by a number of artists of the relationship between imagination and creativity, has proved to be very illuminating in understanding the way all artists work. A scientific look at the imagination tends to focus on our capacity to see things in the mind’s eye in their absence. Yet the visual imagination, as described and used by practising artists, is a much richer and more complex ability, cultivated by artistic training, strongly linked to personality and emotion and often exercised in the act of creation, rather than the ability to visualise something which isn’t there.

The visual imagination is a territory one would expect visual artists to claim and to explain – one might expect them to be able to describe how they use it in their work. But like consciousness it is a slippery concept: you know what it is until you try to describe it. And it has many different narratives, not only because it is necessarily a subjective and individual experience – it is my or your visual imagination that we are talking about – but also because artists, philosophers, psychologists and neuroscientists all have something significant to say about it.

Negotiating all these specialist and different narratives is difficult, but important if we are even to start to find an agreed definition or understanding of what a visual imagination might be. Without a commonality of definition, what is the point of scanning an individual’s brain to see what is going on in there when imagining? First-hand accounts of what a visual imagination means to individual artists are a rich source of information.

When I surveyed my students on Central Saint Martins’ Art & Science MA programme, I found that for some artists a visual imagination is “very different from simply visualising something that exists in the world – which seems to be the most common target for scientific studies of ‘visualisation’”. Some talk about “seeing new work in the mind’s eye” . This is a place in consciousness which does not feel the same as memory: it is fed by images of the world but does not simply reproduce them. The images tumble around with thoughts, ideas and feelings.

The act of drawing might spark off something in one’s imagination – but it is not something you can willfully control. This visual imagination is tempered by the particularity and history of being me. It is necessarily my visual imagination, and it can be part of art school training for an artist to develop their visual imagination by breaking down the editing-out processes we bring to our everyday experiences. Art students are often encouraged to notice and remember things which might otherwise go unnoticed – to become visually hyper-sensitive to the world.

Looking back in history, we find William Blake (1757–1827), the visionary artist and poet, wrote extensively of the imagination, extolling its central role: “The imagination is not a state: it is the human existence itself” (Blake, 1948, p. 418). He gives some insight into the significance of visual imagination in his work in letters he wrote to the Reverend John Trusler in 1777. He describes how the images he had drawn for Trusler’s commission had been dictated by “my Genius or Angel” . Blake wrote “I could not do otherwise. It was outside my power”.

So for Blake, visual imagination was much more than simply being able to picture something from the real world, in the mind’s eye. “But to the eyes of the man of imagination,’ he wrote in a later letter, “nature is imagination itself. As a man is, so he sees. […] You certainly mistake, when you say that the visions of fancy are not to be found in this world. To me, this world is all one continued vision of fancy or imagination…” (Blake, 1799).

Blake’s contemporary Francisco Goya (1746–1828), however, believed that the artist’s imagination needs to be tempered by rationality. As he captioned one of his 1799 Los Caprichos prints, “The sleep of reason produces monsters : Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters ; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and source of their wonders.” (Blake, 1799) Today’s artists echo Blake’s and Goya’s sentiments.

For painter Helen Garrett, a vivid visual imagination is central to her practice:

“As a young artist I became fascinated by the images and characters that were appearing and re-appearing in drawings and I realized they were of a deep symbolism that I didn’t understand, but knew was a part of me also… The imaginative world stood with equal weight as my reality – with its endless mystery and revelation…” (Garrett, 2014)

For illustrator Mary Kuper, imagining is a series of processes:

“These processes of imagining seem interlinked, not discreet separate occurrences. Sometimes one does shut ones’ eyes as it were and see things in the mind’s eye. Mostly though I think it is a fluid process between imagining, creating, revisualising and back again at which point the process is not separable into component parts. The questions seem reductive, like delegating the process of walking to the feet, or knees.” (Aldworth, 2016, p. 175)

Helen Pynor finds visual imagination essential when she starts work:

“It always informs the start of a project i.e. it forms the image(s) towards which I work, at the start of a project. At a certain stage of the making process, something else kicks in. I begin to respond to what the actual materials I’m working with present to me. These materials provide new prompts and new information, that suggest new possibilities I hadn’t thought of, and these become the prompts for the next stages of the work, as well as prompts that my visual imagination can continue to work with and develop. So it’s very much a circular process that continues to feed itself.” (Aldworth, 2016, p. 180)

Mariner Warner observes of the painter Paula Rego that,

“Rego has been making images out of stories since she was a child, and if anything can be said to offer a consistent thread through her fertile and multi-faceted production it is this: she has been a narrative artist all along, and one whose stories are not reproduced from life as observed or remembered, but from goings-on in the camera lucida of the mind’s eye. Rego hasn’t lost in adulthood the energy of the child’s make-believe world: ‘It all comes out of my head,’ she says. ‘All little girls improvise, and it’s not just illustration: I make it my own’.” (Warner, 2003)

For myself, I find that I use my visual imagination as a starting point in making my work. It often involves putting things together which might not exist in the real world. My work is research led – both intellectually and as experiments into what media I might use. After so many years of working, I have many technical skills and visual tricks which also feed into my imagination. It is an imagination with knowledge. I do not think that my visual imagination provides a sudden unique inspiration, it is more considered, more rooted in myself and my culture, but I do float visual possibilities around in my mind.

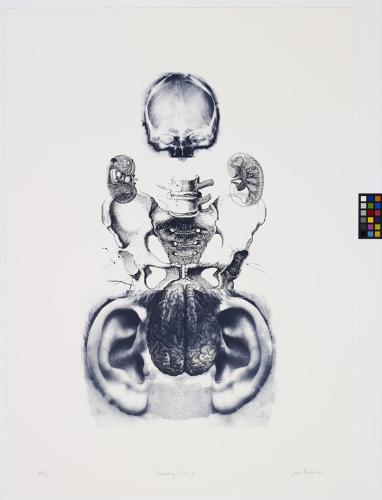

Susan Aldworth, Reassembling the Self 3, 2012. Lithograph. Reproduced with permission of the artist and TAG Fine Arts

Extreme Imagination is a groundbreaking exhibition in that it offers us a unique insight into the process of making. It presents artworks by a number of individual artists who have been identified as having either no visual imagery or a great deal of it. The individual artworks are displayed alongside personal accounts of how present or absent visual imagery was for the artists in their creative processes. These accounts are moving and revealing, and in many cases defy expectations.

Imagination goes well beyond visual imagery. It might seem likely that artists who are aphantasic would create works which are simply representational, and those who are hyperphantasic would create fantasy art. But the works in Extreme Imagination do not fit into any simplistic art categories. They are as varied and various as the artists who created them, and thus ask us to revise our understanding of the role of visual imagination in the creation of art.

References

Aldworth, S. (2016). ‘The art of imagination’. Cortex. Vol 105, pp. 173–181

Blake, W. (1948). Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Geoffrey Keynes (ed). New York: The Nonesuch Press

Blake, W. (1799). Letter to Dr Trusler, 16th and 23rd August, 1799. <https://archive.org/stream/ lettersofwilliam002199mbp/ lettersofwilliam002199mbp_ djvu.txt>

Garrett, H. (2014). ‘Imagination and Art’, Interalia Magazine, April. <https://www.interaliamag.org/ articles/imagination-and-art/>

Hofer, P. (1969). ‘Francisco Goya: Los Caprichos’. New York: Dover Publications Warner, M. (2003). ‘An Artist’s Dream World’, Tate Arts and Culture, 8, Nov.-Dec., <www.tate.org.uk/magazine/ issue8/rego.htm>

The Neuroimaging of Imagery, by Crawford Winlove

To cite this: Winlove, C. (2018) 'The Neuroimaging of Imagery', in S. Aldworth and M. MacKisack (eds.) Extreme Imagination: Inside the Eye's Mind, London: University of Exeter, pp. 36-44.

When you create a visual image in your mind, in the absence of corresponding external stimuli, the parts of your brain which become active can be identified using functional magnetic resonance imaging. These areas are the inferior frontal gyrus, the medial frontal gyrus and the insula. Or perhaps the superior parietal lobule, the precuneus and the gyrus lingualis.

These apparent contradictions, taken from highly-regarded studies of visual imagery that used similar participants and tasks, typify the inadvertent obfuscation that too often arises from neuroimaging research. This confusion has at least two key sources. First, there is inherent uncertainty about the underlying measurements. The magnetic resonance imaging of nerve cells relies upon detecting signals – alterations in blood flow associated with changes in their activity – that differ by about 1% in size to the fluctuations that occur at rest. This is like trying to judge if any pea, boiling and bouncing amongst a group of 25,000 peas, is more than 0.02 grams heavier than the others.

Robust statistical analyses are therefore essential for establishing whether a meaningful change has indeed occurred, not simply a transient fluctuation in ongoing activity. To aid such decisions the statistical analysis of neuroimaging data has increased in sophistication over the history of neuroimaging, but these tech- niques are not always implemented appropriately. The hazards of such errors are striking: Atlantic salmon can empathize with human emotions even after their own death. (1)

The challenges do not stop there. The second important difficulty for neuroimaging manifests in attempts to identify and name brain regions. There is the immediate obstacle that neuroanatomy uses a now unspoken language: for most people, naming the hole in the base of the human skull, through which the spinal cord passes, the foramen magnum loses its instructive power without translation – big hole. The foramen magnum is at least a conspicuous anatomical landmark, unlike many brain structures.

Anatomists in the 19th century recognised that the human brain’s convoluted surface was not random, and struggled with its delineation as their peers attempted a wider taxonomy of nature. Knowledge of the structures they identified proved precarious: the groove which runs along the centre of the fusiform, and segregates important functional sub-divisions, was identified in 1896, forgotten until 1951 – and overlooked again until its final rediscovery in 1996.

It is salutatory to recognise how many apparently new insights are simply rediscoveries of that which has been forgotten. Territorial disagreements also ramify in language, with different terms referring to the same region, or the same term referring to completely different regions. This confounds discussion: how can we judge the role of a particular area in visual imagery if we can’t even agree which locations should share a name? Lists and thesauri have attempted codification and clarification, but the most influential element of standardisation came with the publishing of the Talairach atlas in 1988, especially once computer programmes automated the application of these terms to results.

However, such an approach remained problematic, not least because the atlas is based on the left hemisphere of a single brain, that of a 60-year-old Caucasian woman. It therefore accurately represents neither the wider population nor any other individual. To address this, we have begun to use the anatomical areas and names proposed by the Human Connectome Project (HCP) in 2016. The HCP acquired images from 210 healthy young adults and divided the resulting average into 180 anatomical regions, on the basis of differences in shape, function and connectivity.

This offers, for the first time, a map of the brain that captures much of its magnificent complexity. Let us now return to the opening statements – do the apparent contradictions matter? For the postgraduate student, racing to publish their work to buttress the defence of their thesis, they may seem rather unimportant. For researchers who survive this ordeal, and the much greater challenge of securing academic employment, these differences might even provide a degree of comfort: all parties do not need to agree on all of the details, but can instead accept that each of them is broadly correct.

Nonetheless, objective truth endures: which of these regions really is genuinely active? It is only by answering such questions that we can ensure that our theoretical predictions are subject to the challenge of falsification. It is now possible to identify the regions which are consistently active by combining data from previous studies. This enabled the synthesis of data from 40 different research publications, ensuring the fullest possible insights emerge from the work of other researchers and from the time of the 464 participants.

In our recent study, we used the most popular of these statistical methods for coordinate-based meta- analysis, Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE). The key feature of this approach is that reported points of activation are not treated as definite locations, but rather as the most probable central point in a three-dimensional range of neighbouring possibilities. Thus, the hole on a golf-course should be the most likely place to find a golf ball – but golf balls can be much more widely scattered.

The ALE technique captures this variation, and enables more robust statements about which parts of the brain are active during visual imagery. There are 11 active regions, with some differences depending on the precise task completed by participants. Together, these regions form a network which, through its changing patterns of interaction, gives rise to imagery experiences. The following description concentrates on the most prominent of these regions, those which we believe form the inalienable core of the visual imagery network. It is probable that others remain to be identified.

The greatest activation was in the superior parietal lobule (SPL), which lies at the upper- back of the brain; both sides of the brain were active, but activation was more extensive on the left-hand side. Previous work has linked the left SPL to the generation of visual images, with its activity preceding that of the right hemisphere. Nonetheless, in a demonstration of the brain’s flexibility, its activation is not essential for image generation: when the left SPL is temporarily inhibited using magnetic pulses image generation is just a little slower – but imagery can be stopped completely by also inhibiting the right SPL.

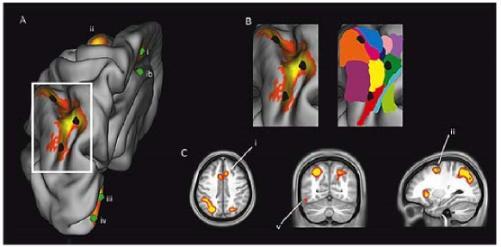

Human Connectome Project template showing some of the key brain regions active during visual imagery

A A view of the left hemisphere of the brain, looking from the back, which shows both the top and the middle of the brain. The white box encloses the superior parietal lobule (SPL, x), which is expanded in panel B to show how it, in turn, contains many more sub-regions. Within panel A, other areas mentioned in the text are also visible. The supplementary and cingulate eye field, SCEF (i) is visible towards the front of the brain, alongside a region we do not discuss, posterior 24 prime (ib). The green dots highlight the centre of the activation, with the orange-toyellow colour gradient showing increasing evidence of overlap. Towards the outer edge of the brain the frontal eye field (FEF, ii) is just visible. At the bottom rear of the brain the primary visual cortex is covered by orange activation, with two individual hot-spots of activation, iii and iv.

B An illustration of the 12 sub- regions of the superior parietal lobule visible from the current viewing position. Each colour depicts a different anatomical area, with the whole area representing about 5cm in length.

C A volume-based depiction of the same data. The first two panels highlight the marked difference in the extent of consistent activation between the left and right hemispheres. Also visible are the supplementary and cingulate eye fields (SCEF, i), the frontal eye fields (FEF, ii), and Area PH (v).

The central importance of the SPL for visual imagery is further supported by its direct connection to most of the regions we discuss next. Several regions at the front of the brain were also active during visual imagery. Until recently only a few sub-regions had been identified within the frontal lobes, so even relatively distant points of activation were attributed to the same rather generic name. The resulting loss of precision made it difficult to distinguish whether particular activations were specific to the process of interest, in this case visual imagery, or simply recurring features of most brain activity.

Using the recently developed HCP Brain Atlas, we pinpointed activation during visual imagery as occurring in the newly identified supplementary and cingulate eye field (SCEF). These lie towards the front and centre of the brain, above the dense network of nerve fibres which connect its two hemispheres; a couple of centimetres below are two of the fluid-filled cavities which allow the brain to float. Previous work shows that the degree to which the SCEF is activated predicts imagery performance. Plausibly, SCEF activity may launch the process of visual imagery, helping to link together components of a wider brain network.

We observed further activation at the front of the brain in the premotor cortex, most notably in the Frontal Eye Field (FEF), which is connected to the SCEF and integrates information to guide eye move- ments and modulate visual attention. Nearby, roughly in line with the SCEF but on the brain’s outer surface, we saw activation of rostral area 6, which processes the sound and significance of language. Moving to the back of the brain, a longstanding point of controversy has been whether regions involved in visual perception are also involved in visual imagery. The human visual system is remarkable for its capability and complexity: there are 19 brain regions involved in early visual processing alone, with many more regions supporting the further processing of visual information.

It seems intuitive that these visual areas would be involved in visual imagery, and such a contention has been central to a popular theory of visual imagery (Kosslyn, 1981). A key tenet of this theory is the activation during visual imagery of the primary visual cortex, but this has only been reported by about half of the related neuroimaging studies. There are many possible reasons for these discrepancies. The primary visual cortex may only be active when participants complete demanding tasks, such as generating images with high-resolution details or making decisions based on their images. It is also possible that the degree of activity seen in the primary visual cortex reflects the vividness of an imagery experience. Given these possible sources of variation, it is notable that we found the primary visual cortex was active, even when participants had their eyes closed.

What is the functional role of the primary visual cortex in visual imagery? Input to the primary visual cortex from across the brain is substantial, but none has the exquisite precision of the input that comes from the eyes. This strongly suggests that the primary visual cortex may not play the literally depictive role proposed in some theories of visual imagery, in which a close correspondence between spatial patterns of primary visual cortex activation and spatial features of represented objects is of central importance (Kosslyn, 1981, 2005). Furthermore, whatever the role of the primary visual cortex in imagery, this appears to be fulfilled largely independently of many other visual areas, none of which were activated in our comparisons.

This may simply reflect the residual variation in the tasks completed by participants, but is a priority for further investigation. One incautious speculation in anticipation of this work is the possibility that the sovereign role for the primary visual cortex could be providing an internal source of vision-like activity that can then be further processed to generate imagery experiences similar to perception. The co-activation of the SPL, and its established connectivity with the primary visual cortex, provides some support for this interpretation. The final areas to discuss are the ventral temporal lobes, which lie at the base of the brain, at roughly the level of the ear canal.

There was activation on both sides of the brain which centred on the recently redefined Area PH, and extended only slightly into its more famous neighbour the Fusiform Face Complex (FFC). Previous work in visual imagery has inaccurately attributed activation to the FFC, with a similar phenomenon in the wider neuro-imaging literature meaning that activity in Area PH has rarely been reported. The function of Area PH therefore remains rather mysterious – but it is striking that, like the primary visual cortex, it too is strongly connected to the SPL.

In conclusion, several insights emerge from our calculations. Visual imagery predominantly activates the left-hand side of the brain, with activation of the SPL suggesting that attentional processes are an important aspect of visual imagery. The primary visual cortex is activated during visual imagery, even when participants have their eyes closed, which is consistent with important depictive theories of visual imagery (Kosslyn, 1981, 2005), though the lack of activation in other early visual areas is surprising.

The activation of frontal areas suggests that language plays a role in the construction and utilisation of mental images, a finding required by propositional theories of visual imagery (Pylyshyn, 2003). The activation of the SCEF and the FEF suggest that eye movements are also important aspects of visual imagery processes, and offer support for often overlooked enactive theories of imagery (Bartolomeo et al., 2013; Thomas, 2003). The intriguing possibility then emerges that the intuitive similarity of visual perception and imagery reflects a common mechanism: both are shaped by our powers of anticipation.

(1) In prècis, researchers at Dartmouth College recruited a single mature Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) which was 45 centimetres in length, 1.7 kilograms in weight – and dead. Using a standard fMRI protocol the salmon was shown a series of photographs, each depicting a human in a social situation. The salmon was asked to identify the emotion that the individual in the photograph was most likely to be experiencing. Each photograph was presented for 10 seconds, followed by 12 seconds rest. Following a common, if rather lenient, statistical analysis they identified a region at the centre of the brain which became active during the task. This might be interpreted as evidence that the dead salmon remained capable of judging human emotion, or that statistical methods are crucial.

References

Bartolomeo, P., Bourgeois, A., Bourlon, C., & Migliaccio, R. (2013). Visual and Motor Mental Imagery After Brain Damage. In Multisensory Imagery (pp. 249–269). Springer, New York, NY.

Kosslyn, S. (1981). The Medium and the Message in Mental Imagery: A Theory. In N. Block (Ed.), Imagery. MIT Press

Kosslyn, S. (2005). Mental images and the Brain. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22(3), 333–347

Pylyshyn, Z. (2003). Return of the mental image: Are there really pictures in the brain? [Neuropsychology & Neurology 2520]. Retrieved from <http:// ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb

Thomas, N. (2003). Imagining minds. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 10(11), 79–84

From Inner Design to Extended Mind: the Aphantasic Artist in History, by Matthew MacKisack

To cite this: MacKisack, M. (2018) 'From Inner Design to Extended Mind: the Aphantasic Artist in History', in S. Aldworth and M. MacKisack (eds.) Extreme Imagination: Inside the Eye's Mind, London: University of Exeter, pp. 45-49

The existence of ‘aphantasic’ artists, who do not experience sensory imagery, might come as a surprise. Surely, to make anything, you have to be able to imagine what the thing will look like. How else does the poet choose the ‘right’ word, the architect the ‘right’ angle? Isn’t that what making art is – having an idea then expressing that idea, realising it in the world?

One would not be alone in such an assumption. It is how artists and philosophers of the Western intellectual tradition have described the creative process for centuries. Aristotle makes what is probably the original statement of it in the treatise we know as the Metaphysics, which was compiled in the 1st century BCE. In line with his doctrine of hylomorphism – that everything is an interaction of matter and form – Aristotle holds that the forms of art pre-exist in the nous or soul of the artist. The architect conceives of the form of the house; the sculptor conceives of the form of the statue.

The creation of the house or statue entails the form entering from the maker into matter. Aristotle’s model, or its general principle, was widely expressed in the European Renaissance of the 15th- and 16th-century. Giorgio Vasari, the artist-biographer, held that drawing originates in the intellect of the artist; the painter Raphael claimed that “in order to paint a beautiful woman … I make use of a certain idea [ certa idea] that comes to my mind” (Arnheim, 1969, p. 98).

Indeed, the ‘idea’ in this sense became a central concept in the period’s discourses on art, in all media. In Elizabethan England it was associated with poetry and poetics, for example Philip Sidney’s notion of ‘fore-conceit’: a conception of the work existing in the poet’s mind before it is written. Back in Italy, the painter and theorist Federico Zuccari, integrating classical philosophy and Christian theology, elevated the artist’s idea to a metaphysical level.

In his L’Idea de pittori, scultori e architetti of 1607 the ‘disegno interno’, the thing in the mind of the artist

which necessarily precedes execution of the ‘disegno esterno’, is a segno di dio in noi: a sign of God in us. Zuccari writes that,

“having created man in His image, [God] wished to grant him the ability to form in himself an inner intellectual Design […] so that with this Design, almost imitating God and vying with Nature, he could produce an infinite number of artificial things resembling natural ones, and by means of painting and sculpture make new Paradises visible on Earth.” (Panofsky, 1968, 88)

For Zuccari, the importance of the internal design cannot be understated: it is what accounts for, and enables, the artist’s god-like capacity for creation. The philosophical and social changes of the 18th- century – the ‘Enlightenment’ – saw the emergence of a distinctively modern, psychological concept of the self. The artist’s idea is shorn of its spiritual aspects and becomes a properly mental entity.

British painter and first president of the Royal Academy, Joshua Reynolds, gave an accordingly precise account of the role this ‘idea’ plays in artistic production, in a lecture of 1771. The painter’s subject, says Reynolds, is given to them by the poet or historian, something from ‘Greek and Roman fable’ or ‘Scripture history’. Hearing or reading the story evokes a mental picture in the artist, which they turn into their painting:

“Whenever a story is related, every man forms a picture in his mind of the action and the expression of the persons employed. The power of representing this mental picture in canvas is what we call invention in a painter.”(Wark, 1997, p. 58)

Sir Joshua Reynolds, A Nymph and Cupid: the Snake in the Grass, 1784 © Tate, London 2014

The artist’s job is to transfer the picture in his mind to the canvas directly. He should paint the ‘general idea’ without ‘minute particularities’ (Wark, 1997, p. 58), that is, like a mental picture – so that seeing the painting is for the viewer as close as possible as to how hearing the story was for the artist. The canvas is essentially a means for communicating the artist’s mental pictures. In this way, Reynolds’s is the psychologically-inflected culmination of a view that had been held for centuries: artistic creation is actually only a technical formality after the formation of an ideal design in the mind; picture-making is purely the externalising of inner pictures.

The 20th-century, however, saw this view begin to be undermined. In Visual Thinking (1969) the psych- ologist of art Rudolf Arnheim argued that reasoning and perceiving are not as distinct as philosophy has traditionally conceived them to be. “[A] person who paints, writes, composes, [or] dances,” Arnheim claims, does not externalise ideas, but rather “thinks with his senses”(Arnheim, 1969, p. 97). Arnheim considers the case of someone drawing an elephant from memory, and observes that,

“[i]f you ask him from what model he is drawing he may deny convincingly that he has anything like an explicit picture of an animal in his mind”. It seems, instead, that the operation, “take[s] place in the perceived outside world, on the drawing board: as the lines and colours appear, they look right or wrong to the draftsman, and they themselves seem to determine what he must do about them” (Arnheim, 1969, p. 98).

While, Arnheim admits, there must be “some standard in the mind of the draftsman” to lead him to judge a certain line as right or wrong, we are very far from a ‘disegno interno’, or indeed Reynold’s ‘mental picture’. Arnheim’s observation that “the operation seems to take place … on the drawing board” is, I think, quite radical – and it predicts a view of drawing, and creativity more generally, that leads from an influential early-21st-century philosophical position.

This is the idea that cognition, human thought, is not limited to what takes place inside the skull, but can reside in processes in the outside world. When tasked with remembering, calculating, reasoning, and so on, humans consistently use some part of their environ- ment to do so. We use a pen and paper to perform long multiplication, we physically rearrange our Scrabble tiles to help us think of a word: two examples of ‘extended cognition’ that Andy Clark and David Chalmers give in their 1998 paper that first presented the idea.

These are situations in which the individual brain performs some operations, but delegates others to physical manipulations of external media. It thinks ‘with the world’. Alongside the mathematician’s pen and paper and the Scrabble player’s row of tiles we should also consider, Clark claims in a later work, the artist’s sketchpad. Why, he asks, do artists sketch at all?Why not simply imagine the final artwork ‘in the mind’s eye’ and execute it directly on the canvas – as indeed Joshua Reynolds had advocated? Because, according to Clark, mental visualisations are ‘interpretatively fixed’: they are what the visualiser makes them to be.

By starting to draw, however, the artist begins a feedback loop, in which each mark they make suggests possibilities for the next. The artist “perceptually, not merely imaginatively, re-encounters visual forms, which she can then inspect, tweak, and re-sketch” . In this way the sketch pad, claims Clark, is more than just a tool: it is actually part of a “unified, extended cognitive system”, a way of manipulating data that “the biological brain would find hard, time consuming, or even impossible” (Clark, 2003, p. 76).

We arrive at a point where creativity, as exemplified by drawing at least, needs little ‘inner design’, and certainly no ‘mental picture’. The artist does not externalise a thought: thinking takes place on the canvas. What, then, does the preceding historical sketch tell us about aphantasic art? Are we any closer to understanding how someone can create something without an idea of what it will look like? What we’ve found is that in modern conceptualisations of the drawing process – Arnheim’s and Clark’s – “visualising is not part of the process”. The artist works ‘perceptually’, between what they have already drawn and “some standard in the mind” – neither of which is touched by aphantasia, so the inability to visualise is no impediment.

Furthermore, Clark’s model is based on the limitedness of imagery per se, disregarding individual differences. But the aphantasic’s imagery is worse than limited – it is wholly unavailable. They, especially, are obligated to make marks “in the outside world” if they want to know what the thing they are thinking of looks like. They can fairly be said to have extended their minds to include the paper because it is used for something their brains in particular find impossible. Here “thinking with the world” is a means to accommodate an individual difference, like using the verbal system for a spatial task, as aphantasics also appear to do (see Zeman 2010).

So what happens to the ‘externaliser’ thesis? Do we disregard it as outdated or incorrect? No – we look at the reasons those holding to it had for doing so. For Reynolds, it was the weight of tradition and the influence of Empiricist philosophy, but also his own psychological make up. There are clear suggestions that Reynolds himself experienced vivid mental imagery: assuming that ‘every man’ forms pictures in his mind when hearing a story, quite possibly, because he is taking his own experience to be everyone’s.

Imagery experience leads to an imagery disposition: that is to say, if you have it, you use it (and if you don’t, you develop other means). Now Reynold’s theory of externalisation makes more sense: it is how he works (and so how his students should work). We approach the possibility, in conclusion, that the two theories represent two different ways of working, informed by religious and philosophical beliefs of the time, but also by the mental make-up and predispositions of their adherents.

References

Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual Thinking. Berkeley: University of California Press

Clark, A. (2003). Natural-Born Cyborgs: Minds, Technologies, and the Future of Human Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Panofsky, E. (1968). Idea: a Concept in Art Theory. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press

Wark, R. (ed) (1997). Sir Joshua Reynolds: Discourses on Art. Yale University Press

Zeman, A. Z. J., Della Sala, S., Torrens, L. A., Gountouna, V.-E., McGonigle, D. J., & Logie, R. H. (2010). Loss of imagery phenomenology with intact visuospatial task performance: a case of ‘blind imagination.’ Neuropsychologia 48, 145–155

Extreme Imagination and the Emotions: Examples from the Middle East and the United States, by John Onians

To cite this: Onians, J. (2018) 'Extreme Imagination and the Emotions: Examples from the Middle East and the United States', in S. Aldworth and M. MacKisack (eds.) Extreme Imagination: Inside the Eye's Mind, London: University of Exeter, pp. 14-20

The use of the imagination varies between individuals. Indeed, as Adam Zeman has shown, it is now possible to say that some people are aphantasic, that is are incapable of visual imagination, while others are hyperphantasic, that is possess a visual imagination that is highly developed, and it is possible to correlate the distinction with differences in brain activity. It is also possible to talk of less extreme variations in the use of the visual imagination. Some people seem to use it more than others and some use it differently at different times. And the same is true of whole cultures. Some seem to exploit the visual imagination much more than others, and even within a cultural tradition the exploitation of the visual imagination may vary.

How can we explore such variation? In time it will be studied using elaborate resources, such as psychological tests, brain-scans, and questionnaires; for the present perhaps the best we can do is seek to establish some of the patterns behind the variation. One way to start is by comparing variations between cultures to variations between activities in the life of an individual.

Take Leonardo da Vinci, for instance. The Florentine painter is famous for having made anatomical drawings which are much more accurate representations of what we see when we look at the body than anything made earlier. However, he is equally famous for having recommended a thoroughgoing use of the imagination, as when he tells the artist who needs to invent a new composition that if he looks at dirty or stained walls he will see “various battles and figures darting about, strangelooking faces and costumes, and an endless number of things” (Kemp, 2001, p. 222). Here he relies entirely on the imagination, because these ‘things’ that he sees come not from the wall he is looking at, but out of his head, a point he emphasises by comparing the viewer’s response to a stained wall to a listener’s response to the sound of church bells, “in whose peal you will find any name or word you care to imagine” (ibid.). In these two cases what you see or hear depends entirely on what you want to see or hear. Evidently, in the anatomical drawings Leonardo completely suppresses his imagination. In the context of composition he gives it full rein.

This example of a polarisation in the engagement of the imagination between two contexts within a single artist’s work can be seen to have its parallel in comparisons between two cultures. In ancient Greece, for example, most art appears as the transcription of sensory experience, both visual and tactile, and there is little that can be seen as the product of the imagination.

The same is not true of other traditions, where such transcriptions are rarer and the use of the imagination more obvious and frequent. In the Middle East, for example, the importance of the imagination is particularly striking. Thus, in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, completed 691, there was, until recently, a sheet of marble whose natural veinings were seen by Muslims as a representation of their hero Saladin. Because the figure that Muslim visitors to Jerusalem most wanted to see was the hero who had liberated it from the Christians, his was the face they imagined in the marble.

There is also another example of the power of what we can call a particular ‘Middle Eastern’ imagination in a similar context in recent history. Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, aspired to a role comparable to that of Saladin, and he exploited his people’s heightened imagination by habitually draping his headscarf in such a way that its outline corresponded to the map of the Palestinian state of whose establishment they dreamed. The imaginative act of seeing the scarf as a map, like that of seeing Saladin’s face in a slab of marble, was emotionally driven. Those who did not desire a Palestinian state were less likely to see the correspondence.