The US Presidential Election and the potential for Trade Wars

Published: 6 November 2024

6 November 2024: University of Glasgow Principal and Vice-Chancellor Professor Sir Anton Muscatelli writes about the results of the 2024 US Presidential Election, warns of the potential for future trade wars, and notes it is now imperative that the UK re-evaluates its alignment with the EU as a large trading bloc.

Blog by Professor Sir Anton Muscatelli, Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Glasgow

The return of President Trump to the White House took many pollsters by surprise. As in 2016, the pre-election polls seem to have underestimated the appeal of his message with the US electorate, particularly on the economy. With a Republican majority in the Senate, and the House of Representatives still on a knife-edge at the time of writing, President Trump might have considerable control over the levers of economic policy.

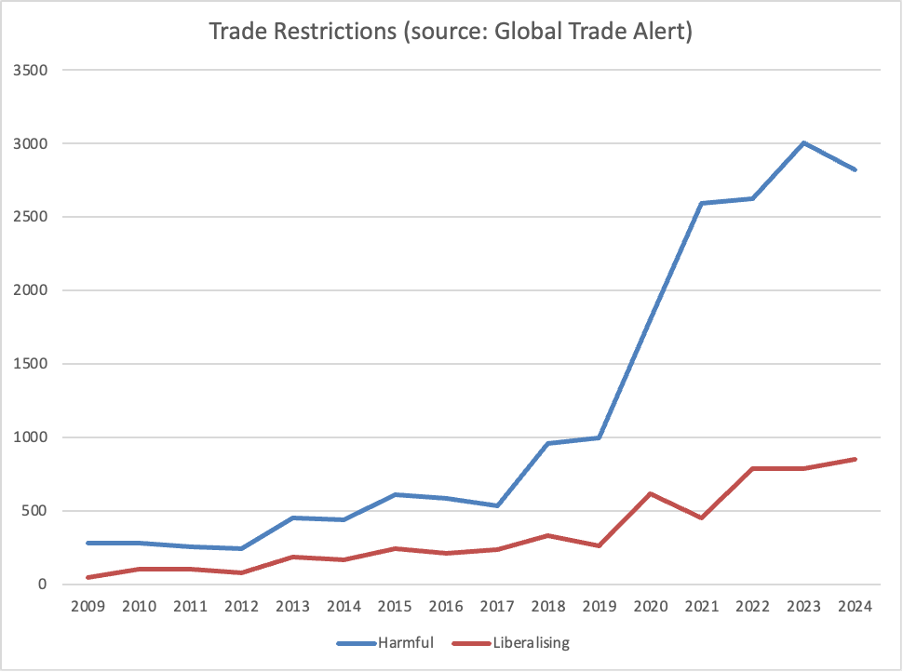

Between 2016-17 and now, the world economy has been hit by many interventions which have restricted trade rather than liberalising it. The Global Trade Alert documents these interventions, which range from tariff measures to subsidies and export-related measures, and trade-related investment measures. The chart shows how we have seen a return of protectionism to the global economy.

Of course, one has to be careful in assuming that what is said in the heat of an election campaign will actually be implemented. Understanding the impact of trade restrictions is complicated, for several reasons.

First, like taxes, the incidence of trade protection measures like tariffs is sometimes more complex than politicians assume. A study from 2020 on 2018 data showed that the costs of US tariffs were passed on entirely to US businesses importing goods and consumers rather than lowering foreign prices, which was the original intent. Second, as pointed out by many expert trade observers, the initial post-2016 US-China trade war focused selectively on some products (especially some consumer electronics and IT products, and semiconductors) but in other sectors trade between the two countries continued to grow. As a whole, China-US trade fell back. Third, there is strong evidence that the trade system adapted smoothly to the US-China trade war, with production in more restricted products like electronics routed to the USA via third markets, like Vietnam, Taiwan, Thailand, Mexico and even European countries. In essence, the US-China trade war ended up re-shaping global supply chains to avoid restrictions.

The question is whether the 2024 election bluster will simply lead to more of the same. There are reasons to be more worried on this occasion.

First, there is a sense in which a second Trump Presidency might be less moderate on trade than in 2016. The economy was a major issue on the electoral agenda and this time the new US administration may go further. It may target more countries rather than just China. Indeed there are real concerns in Europe regarding potential for more US protectionism.

Second, there are nightmare scenarios which haven’t played out yet, but which are not inconceivable. It is worth noting that protectionism is not simply a Republican concern and there have been major issues with the WTO dispute settlement procedures which did not improve in 2020 under a Biden administration. But whilst a Harris presidency might have helped with the current discussions on reforms to settle WTO trade disputes, a Trump Presidency may well further entrench the stalemate at the WTO.

As the IMF warned in 2023, the global economy is facing the risk of a much more serious geoeconomic fragmentation, i.e. the break-up into separate trading blocs where trade flows between blocs is reduced markedly. One could imagine separate blocs emerging around the USA and China for instance, with countries having to choose which bloc to belong to or trying to steer a middle course. Or an even more drastic fragmentation which even involves the USA and Europe separating out in key technology sectors. The impact on global living standards of such drastic geoeconomic fragmentation is potentially huge. IMF economists have estimated the impact on the world economy of such an event as similar to that of the Covid pandemic, with losses of 2-4% of global GDP. Unlike the pandemic, however, these losses would be permanent.

A number of economists at the WTO have produced similar estimates, also looking at an upside: positive scenarios which might come from a global revival of multilateralism against greater geopolitical rivalry. Their estimated impact from fragmentation is even greater than the IMF figures, ranging from 6.4% of GDP for the advanced economies to 10.2% for emerging markets and 11.3% for low-income countries.

Whether these estimates are close to the mark is not the key point, however. The major issue is that the US election should be a call to policymakers outside the USA to actively consider what might happen next.

For the UK, since we left the European single market and customs union it should focus our mind of what the best strategy might be, should there be a drift towards greater trade fragmentation. My own view is that, unless you are in a very large hypercompetitive flexible wage economy (which the UK is not), you may want to stick more closely to one of the larger blocs in any future trade war.

It is surely imperative that we re-evaluate our position in terms of the UK’s alignment with the EU in key technologies and sectors where we do want to be as competitive as possible.

Author

Professor Sir Anton Muscatelli has been Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Glasgow since 2009. An economist, his research interests are monetary economics, central bank independence, fiscal policy, international finance and macroeconomics.

First published: 6 November 2024