Walking the Antonine Wall

Published: 28 March 2024

Action to Protect Rural Scotland (APRS) Director Kat Jones on her walk of the Antonine Wall from Kilpatrick with UNESCO RILA team members, as part of her Glasgow Green Belt walk series

By Kat Jones

APRS Director Kat Jones is spending some of her weekends and evenings exploring Green Belts with the aim to circumnavigate greater Glasgow and surrounding towns. In this section she walks part of the Antonine Wall from Kilpatrick and finds how much of our own infrastructure and landscape today relates to Roman civil engineering.

I’ve been rather dreading finishing the full circumnavigation of the green belts of Glasgow, which I am enjoying so much. I enjoy every part of it – pouring over the map (now on a small screen on my phone or laptop), plotting a favoured route, looking up walks that may be online in the area, spotting places to visit. I love doing the walks, and I even enjoy the writing up.

I am now perilously close to the end, having reached Cochno, just north of Bearsden and Faifley, a mere 20km from my home, where I began, back in July.

A few weeks ago, a new project came galloping to my rescue. During a late-night chat over dinner with a friend, we developed the kernel of an idea for a walk along the route of the Antonine wall, the northmost frontier of the Roman empire, which happens to pass by less than a mile from my house. Alison holds a UNESCO chair at Glasgow University and, with the Antonine wall being a UNESCO World Heritage site, and passing through a lot of green belt on its way from Old Kilpatrick in the west to Bo’ness in the east, we decided to mix my new hobby with her sabbatical.

![]()

We’d start with a recce, a walking workshop, (a walk-shop?), to explore, literally and metaphorically, what a coast to coast walk along the route of the Antonine wall could look like as a participation project. Unlike the Hadrian’s wall, there is no long-distance route that follows the route of the wall, so we’d need all the skills I’ve gained in peri-urban adventuring on my green belt walk.

In one of those wonderful coincidences, as I drove to meet Alison and two of her team, ‘Start the Week’ on Radio 4 was discussing the legacy of the Romans in Britain, with an author, and the curator of a new exhibition at the British Museum. As I parked up at the Roman bath house in Bearsden, I was listening to them chat about how common nit combs are in Roman finds and even mentioned he Antonine wall in he context of the high quality of objects in regional museums.

With chat about a legionary’s shield, found preserved, complete with painted leather in Syria, ringing in my ears, I jumped into Alison’s car with Bella and Jen from her team, who work with artists, and partners all over the world on the team’s work on refugee integration through languages and the arts.

![]()

We started at Old Kilpatrick – the point at which the western end of the Antonine wall met the Firth of Clyde, which is also the point at which my last walk descended from the Kilpatrick hills before climbing up to Cochno. In planning terms this walk was easy – the route of the wall is marked the whole way on the OS map 1:25,000 and so that’s where we would go.

The point where the Antonine wall met the west coast of Scotland, is right next to the sea lock on the Forth and Clyde Canal at Bowling. I’d become quite interested in the relationship of the wall and the canal: close to my house, the Antonine wall runs parallel to the Forth and Clyde Canal, so I followed the line of the Antonine wall on the map. It runs within a kilometre of the Forth and Clyde Canal (and considerably closer for much of this distance) for 20 miles from Bishopbriggs all the way to Falkirk, where the Union Canal joins the Forth and Cycle Canal. It’s hard not to assume that Roman civil engineers read the landscape in planning their route in much the same way as the engineers of the Canal.

The issue with starting our walk at the Roman fort at the Bowling basin, however, was that the fort is now under a set of decaying warehouses surrounded by galvanised steel intruder fencing, and a street of houses called, appropriately, ‘Roman Crescent’. The route then crosses the railway and the dual Carriageway of the A82 in close succession with no way of getting across.

We therefore, decided to start from a car park regularly used by walkers heading up to the Kilpatrick Hills. To our great delight, the Clyde Coastal route was marked from the car park and took us under the carriageways of the A82 and pretty much in roughly the right direction to follow the Antonine wall.

The Clyde Coastal path is a rather mysterious long-distance path which somehow missed the cut to be one of ‘Scotland’s Great Trails’, a website created about a decade ago to bring together Scotland’s long distance walking routes. It is also not on any maps. I’ve come across sign posts to it at various places I’ve walked over the many years: during a walk near Cochno during lockdown when it had taken me past some cup and ring marked rocks, seen signs for it in walks at Mugdock Country Park, just north of Milngavie, and even seen one of its signs directing walkers over the A809 as I’ve driven past on many occasions.

![]()

Starting along the Antonine wall at Old Kilpatrick. We are exactly over the route of the wall at this point according to our maps.

I was pretty pleased that, at last, this was my chance to walk a chunk of the Clyde Coastal route. But the access to the track at that point wasn’t obvious. We decided to stay true to the line of the wall as much as possible, so we climbed a low fence and headed up the middle of a rising field. The OS map said we were right on the wall but we couldn’t see any imprint of it in the landscape – many years of ploughing must have erased ditch and rampart.

We crossed a ploughed field in the tractor tracks, walking towards a gate which sat exactly on the route of the wall.

Alison and I chatted about the plan for the walk and we had just noted that having an archaeologist along with us would be essential, when we noticed that, scattered through the freshly-tilled soil, were little fragments of china, glass and pottery that had been turned up by the plough.

“We should be field walking, looking for treasure,” said Alison as she bent down to pick up fragments of that blue and white patterned china, willow ware – it was absolutely everywhere. One textured piece of white china turned out to be a small statue with the head broken off when I’d rubbed off the clumping earth. I bent to pick up a metal ball around 2cms across with concentric ridges, perhaps iron, perhaps copper. “That looks interesting,” said Alison.

Having suddenly bitten the bug of amateur archaeology, even if it was just the remains of a Victorian rubbish tip, when I got home I joined an amateur metal detecting group on facebook so I could post up a picture of the metal ball. Consensus was that it was a finial – perhaps part of a fireguard, or a decorative fence. Not Roman then.

We definitely need an archaeologist on this trip.

As a teenager I’d got really interested in Archaeology, I’d visited Herculaneum, Pompeii, Saxon ship burials, and cycled round every dolmen in Jersey. I heard that a dig at one of the Dolmens needed volunteers, and I showed up eager and ready to discover a burial chamber or a horde of flint axe heads. I was given a postage-stamp trowel and a brush small enough to clean a child’s teeth, and told to brush dirt onto the trowel and put it into a bowl. When the bowl was full (which took an inordinate amount of time) I was to sieve the dirt onto the pile. I looked around for the earth moving machines, even the shovels, but there were none. I crouched in my trench under the boiling hot sun. The minutes dawdled by, the hour hand of my watch stubbornly refused to shift. I think I made it to lunch break, or perhaps even the end of the day.

That was the moment when I decided that archaeology was not to be my calling. I returned to the arms of ornithology (my love since the age of 5 and subject for my eventual PhD) like the prodigal son, full of contrition that I had been led astray by the temptations of archaeology.

Look Roman bricks!

Look Roman cobbles!

Look Roman road!

In the absence of seeing evidence of the Antonine wall in the landscape thus far, Alison had started throwing out declarations of antiquity for everyday objects. We’d rejoined the Clyde Coastal route on a track at the top of a cemetery. It followed the route of the Antonine wall exactly, according to the map, with hedges marking either side. We presumed that this section of the wall had escaped becoming part of the cemetery or part of the field for virtue of being the Antonine wall, or perhaps the foundations of the wall had been valuable hard-standing for the track.

![]()

We definitely needed an archaeologist.

At a locked gate we climbed over with the help of a helpfully-placed milk crate, another example of the home made access infrastructure I keep seeing on my green belt walks. When I’d climbed over I noticed that the crate was tied to the fence post with a bike lock. There must be a story behind that bike lock, I thought, imagining a war of attrition between farmer and determined gate-climber.

At the edge of Duntocher, we had our first view of the form of the Antonine wall, a distinct elongated hump in a field of rough grassland next to a 1970s housing estate. As we stopped to photograph it, and a flagpole of multiple signposts, we saw a large transit van from a local tyre workshop. It had stopped in the small dead-end lane completely blocking it. This was a lane to nowhere – just the field we stood next to – and I immediately wondered if he was here for some fly tipping. As we stood and chatted he turned his van around and waited. As we stood longer speculating on what he was doing, he eventually left. Presumably to find a quieter spot with fewer witnesses.

We marveled at the road through the housing estate which was built exactly over the route of the Antonine wall. I wanted to ask someone I saw whether they’d ever found anything Roman while digging their garden? Did they even know that their front garden lay on the Antonine wall? It was here we found the first sign marking the route of the wall, it was a small, faded square sign on a pole holding two road names, both which had worn off completely.

![]()

The gate onto Goldenhill Park which lies on the line of the wall at Duntocher. The Roman fort is at the top of the green rise ahead.

The road followed the route for around a kilometer through Duntocher, and ahead we could see the hill marked on the map as a Roman fort – right in the middle of the town. A path through some greenspace took us to a pedestrian bridge over the Duntocher burn where we could see a lovely old bridge spanning the burn at a huge bedrock outcrop which held the middle base of the bridge.

It was at exactly this point that the Antonine wall also crossed the burn – a crossing point that had evidently been used for millennia.

At the war memorial we headed up the hill towards a square of railings surrounding something that looked very interesting – “Have they fenced in some black bin liners?” asked Jen, noting the pile of rubbish sacks within the fencing. The railings encompassed some of the excavated wall foundations. It was just a square of stones, rather like a very rough patio, and the railings were engraved with Roman units of measurement: Cubitus (cubit), Gradus (pace), Palmipes (foot and Palm), Pes (foot). I found that out from the internet, my first thoughts were that they were the names of Romans who had passed this way. (More evidence that we were in desperate need of an archaeologist).

On the top of the hill, strips of unmown grass indicated where the walls of the fort would have been – I wondered how the mowers knew where to mow and where not to mow. Just past the crest of the hill a new playpark had been built – “Duntocher Fort” said the wooden entrance arch.

![]()

Enclosure of a small area of wall excavated. The words cut into the railings denote the Roman measurements of length.

A couple of weeks later we met Séverine Peyrichou and Stephen Balfour of the ‘Rediscovering the Antonine Wall’ project, with Ríona McMorrow of Historic Environment Scotland at another of their Roman-themed playparks at Auchinstarry. Their 5 year project aimed to bring the history of the Antonine wall to life for local people and create a few key sites that could attract visitors. They took us for a walk over Croy hill to see some of the installations of the project including a giant corten steel legionnaire’s head looking down the route of the wall towards Castle Carey, which became a local landmark during lockdown, and one of the carved distance stones recreated and placed where they had been found along the route of the wall. They also shed some light on the black bin bags

“Ah that must have been just after we did the clear up and the bags hadn’t been collected yet,” they laughed

While Bella bounced on the trampoline under the disapproving gaze of two six-foot high wooden Legionaries, chat turned to the meaning of place names. “Duntocher means Fort on the causeway,” said Jen, who comes from Bearsden, the terminus of this section of our walk. There must have been enough of the causeway and fort left at the time those who named the area lived here we posulated.

The Antonine wall took a dog-leg at this point and turned to the north east to continue through Duntocher and towards Bearsden. We walked through another estate, across a road and rejoined the wall along the path of a die-straight road with fields on one side and a golf course on the other. There was definitely a theme with roads and tracks following the line of the wall exactly. I speculated that the foundations of the turf and palisade structure must have provided a strong base for a transport route. Later, when we met the Antonine wall team, Séverine explained that a military road would have been built just behind the wall to provision the , which, in many cases could have remained as a road over the millennia

Where’s an archaeologist when you need them?

“My stomach is starting to growl louder than the conversation,” said Bella, as we looked for somewhere to stop for lunch. A bench just the other side from a fairway and a putting green was calling to us, so we shuffled through an overgrown hedge, looked both ways for golfers and scuttled across to the bench.

![]()

A single golfer walked towards us as we unpacked the sandwiches. “Nice day for a walk ladies,” he said and teed off from a spot right in front of the bench. We applauded as the ball rose into the sky and fell onto the green at the top of the hill.

Alison started to unpack a tiny and exquisitely decorated Eritrean coffee set onto a tea towel.

Tea time! She said and poured aromatic chai into the little cups. I looked a bit puzzled – why the tea?

“Alison’s Wander-land,” she said.

Some realisation started to dawn.

“Alice-in-Wonderland? …..teaparty..…?” she added for clarity.

Next to the tea set she laid the beautifully embroidered bag, in which she had carried the cups. Alison explained that the embroidery was from Palestine and an example of their traditional patterns which, in 2021, was inscribed on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

“The coffee ceremony of Eritrea should soon become designated,” said Alison, referencing my slight coffee addiction. I wondered aloud whether a coffee ceremony might feature in one of the future UNESCO Antonine Wall walks. Fortunately Alison has someone from Eritrea on her team. “Let’s do it!” she said.

The only bit of the walk which wasn’t on a path or a road was a small detour off the Clyde coastal route to climb another hill with a fort on, ringed with beach trees.

![]()

The line of the Antonine Wall followed an overgrown hedge that rose in a perfectly straight line ahead of us and we headed down a dip through hawthorn scrub and over a small burn before crossing a road and climbing a short wall to a track that took us to the fort. There were no markings and also it seemed not many people came here – the paths weren’t well-trodden, despite us being only 200m from the edge of Bearsden.

I used google aerial photos to find a way into the housing estate – you can always see the desire-lines on an aerial photo – and found a way in, around a boarded-up stone farmhouse that, puzzlingly someone hasn’t thought to convert into flats yet.

![]()

It was then straightforward walking to get to the Bearsden Bathhouse. In two places the line of the wall was preserved within the housing estate – one a linear park with a path in the middle, and trees on either side – a sign told us that it was the line of the wall. And secondly, a hidden woodland full of snowdrops that sat between the back gardens of two set of Victorian villas. I’d seen it on the map and wondered whether we would be able to walk through and, sure enough, between two bungalows a set of concrete steps, very low key with no signage, led us up to the wood. We walked up to what was evidently the ditch and rampart and walked along it for around 200m before plunging back into housing estate. The wall went along under back gardens almost all the way to the bathhouse from here and I wondered whether this was part of the planning – going through gardens rather than under the houses. But we really needed an archaeologist to tell us that….

Finishing at the remains of the Bearsden bath house we sat in what, 1880 years ago, would have been the complex’s cold bath, and chatted about militarisation, the Roman Imperial project, immigration, and what a shared walk along the rest of the Antonine wall would be in the context of Alison’s work on refuge, refugees and the arts. For me the walk would simply be another chance to walk a landscape and find the stories that reside there.

![]()

POSTSCRIPT:

A couple of weeks after this walk, I set off to find where the Antonine wall meets the river Clyde. From the Dumbarton road in Old Kilpatrick, I walked along a row of tenements to meet a path along the canal. In a monumental coincidence, the only bridge over the canal for a kilometre in each direction crosses at the exact point that the canal was dug across the route of the Antonine Wall. It’s a shallow-arched iron bridge with wooden treads and a geared mechanism for raising and lowering the platform to let boats through.

![]()

An old black and white photo was mounted on a new sandstone wall facing the bridge, part of the interpretation for the ‘Rediscovering the Antonine wall’ project. The photo showed an excavation of the wall which took place in the 1920s. The Antonine wall ran just to the right of where I stood, cutting through a row of rickety wooden sheds and garages with very solid looking locks. The shed sitting right on the spot where the wall’s excavation had taken place had a small metal sign above the door. “A man’s home is his castle but a man’s garage is his sanctuary”.

I admired the construction of one of the garages which was made of a collage of red newsagent shop signs and chipboard, and then turned back to the interpretation. A replica of one of the distance stones, dedicated by the 20th Legion, who had constructed this part of the Antonine wall, was inlaid into the sandstone wall. It showed the goddess Victory reclining with a palm branch and a laurel wreath. The replica had been carved by three stone-masonry students from the City of Glasgow College.

![]()

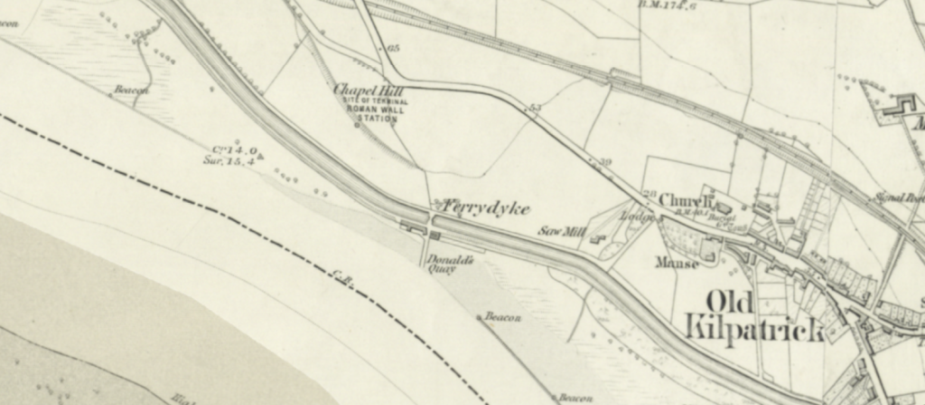

I crossed the bridge over the canal and, instead of following the tow path along, I went straight through scrubby woodland, thick with hawthorn and sycamore, to look for Donald’s quay, the site where the Antonine wall met the Clyde. A 19th Century map I looked at labelled the, now ruined, cottages and buildings as ‘Ferrydyke’ and Wikipedia confirmed that Donald’s quay was the site of a ferry across the Clyde as well as, once the canal was built, a wharf for offloading coal to barges on the canal.

It was getting stormy and, as I peered over the huge sandstone blocks to look at the red light tower, a gust of wind took my breath and whipped my hair across my face. Looking downstream towards Dumbarton, and the mouth of the Clyde, I couldn’t make out where the grey waters ended and the grey sky began.

I walked westward through the narrow woodland between the canal and the river, and a few things started coming together in my mind – a ferry crossing that predated the canal, a bridge built to allow people to continue to access the ferry once the canal was built. A spot in the river for a wharf that could take coal ships right up to the land, even at low tide. The landforms that made this a good ferry crossing point in the 18th and 19th centuries, and a good place for loading and unloading great ships, would presumably have been the same in Roman times. Maybe the co-incidence of a pedestrian bridge over the canal on the very line of the Antonine wall was not a coincidence at all. Maybe it was determined by the landscape. Maybe it was the will of the landscape.

At the outflow of a grand 19th century culvert I scrambled down to the shoreline which was strewn with huge trunks of, what must have once been, splendid oaks. Little foot-high cliffs of crumbling sand, topped with grass, marked the edge of the land. One or two tiny islands had broken away into the estuarine mud, looking rather like a couple of spiky-haired muppets buried up to their noses. As the land eroded, a small saltmarsh was forming – spears of lime green rush were growing up through the sandy mud on the edges of the blobs of existing saltmarsh.

The wind was driving breaking waves onto the shore which gave the feel of being on wilder shores, even though it was only 400m to the Renfrewshire side of the Clyde. There was so much more detritus washed up than I had ever seen on a beach. Dunes of reeds and sticks filled every gap between the huge trunks, and an entire alder tree, roots and all, lay half in the water. A couple of magnificent beams, at least ten meters long lay, almost pristine, surrounded by the splintered and rotting remains of the pilings and piers that must have once stood here at the terminus of the Forth and Clyde canal.

One of the great oak trunks had been buried vertically into the sand and mud leaving about 8ft exposed – at least I assumed it must have been placed there and hadn’t grown here on the shoreline, squeezed between the canal and the Clyde. Where the bark had come off some letters were carved in a scrolled script. I spelt out the letters – A-R-T. Then what was that? Was that an H and a U? It took me far too long to work out that it said Arthur.

Walking round the tree to the other side I nearly jumped out of my skin to find the face of an old bearded man staring back at me. The long carved face and beard curved with the tree along the full length of the trunk. Further along the beach a log more than a meter in diameter with a bolus of tangled roots at the end had been carved into a bench. Three leaves were carved into the seat, the back rest bore two dragonflies. But it was sitting at an angle, washed over a lip of the beach so I couldn’t test it for comfort.

![]()

At the end of the beach I scrambled up a bank and back onto the canal side just at the Bowling basin, where the sea lock holds the canal’s fresh water back from the saline water of the Clyde.

It was like emerging in a different world.

A dozen yachts were braced against the wind in the canal basin, by the sea lock, their mast stays whistling and singing. This small marina was part of some fantastic regeneration work done at the Bowling basin over the past 20 years. On my side of the canal a café and a bike shop were set into the arches under the old viaduct. And the viaduct had been restored to carry bike traffic and pedestrians across the canal and onto the disused railway for the next section of the cycle route to Loch Lomond. I ducked into the warmth of the café and ordered a baked potato.

![]()

![]()

If you’d like to read about the other Green Belt walks you can do so here

![]()

Source: APRS news

First published: 28 March 2024