Improving emerging infectious disease surveillance

Our One Health experts’ depth of experience has enabled them to put forward a new approach to combating emerging infectious diseases.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers at Glasgow have worked together to publish an article in Science, arguing that local capacity strengthening is key to tackling emerging infectious diseases.

The paper was led by Dr Jo Halliday and co-written by some of our key researchers involved in One Health. These are Dr Katie Hampson, Dr Tiziana Lembo, Professor Dan Haydon and Professor Sarah Cleaveland from the Boyd Orr Centre of Population and Ecosystem Health and Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine; and Professor Jo Sharp and Professor Nick Hanley from the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences.

The collaborative approach followed to write this article, and to perform many of the research projects that have informed this work highlights the interdisciplinary way in which Glasgow scientists are tackling global health issues and underlines our dedication to the One Health approach to research.

Why are emerging infectious diseases a threat?

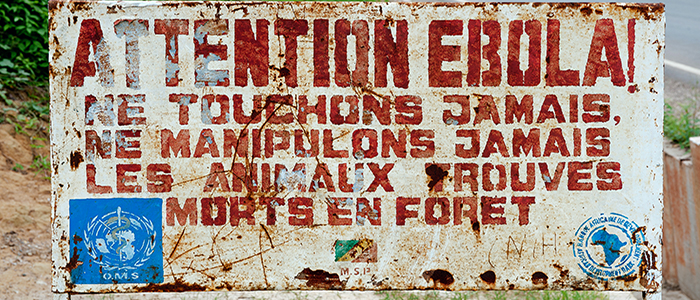

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), such as Ebola and foot-and-mouth disease, threaten the health of humans, animal and crops globally. This threat is exacerbated by the fact we have limited ability to predict when and where new outbreaks of disease will occur.

The current public health capacity and ability to detect and deal with EIDs is weakest in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Unfortunately, this is where many of the factors that contribute to the emergence of infectious diseases tend to converge. Some of these factors include deforestation, rapid urbanisation and agricultural intensification. Wildlife-associated EIDs also tend to occur more in LMICs in environments where human, livestock and wildlife populations live in close proximity. Due to poor public health capacity, it is sadly also the case that the impacts of EIDS are likely to be greatest in LMICS.

It is therefore important to focus efforts on improving surveillance in LMICs in order to catch the emergence of diseases early on and effectively deal with them before they spread. Although there is a widespread awareness of this need, up until now, there has been less clarity on how to go about achieving it.

Our researchers have now put forward an effective way to tackle this challenge.

Looking at the local context

Dr Halliday and our other researchers argue that surveillance systems that have already been put in place to monitor possible outbreaks of a specific local disease can in fact be utilised to tackle EIDs as well.

"We argue for an approach whereby gaps in EID surveillance capacity are filled by responding to local health challenges rather than a focus on EIDs specifically."

The idea that existing capacity can be adapted to respond to new threats is well established. One example of this is laboratories that were put in place to tackle Polio have expanded to cover other diseases such as haemorrhagic fevers, Japanese encephalitis, severe acute respiratory syndrome, H5N1 influenza and the Ebola virus disease.

Likewise, in the veterinary sector, infrastructures that were put in place in Africa to combat Rinderpest, an infectious viral disease in animals that has now been eradicated, have gone on to be used in the battle against Rift Valley fever, peste des petits ruminants, avian influenza and foot-and mouth-disease.

In this article, Dr Halliday and colleagues argue for an approach that intentionally focuses on building capacity to address the current surveillance needs relevant to communities, in a way that maximises the flexible core capacities of such system so that they can be adapted to tackle unknown future threats.

Through focusing on a locally relevant disease, it is possible to capitalise and expand on the positive processes and collaborative networks that are already in place. This will, in turn, foster the continued engagement of the local community. This approach also provides a way to build communication platforms, networks, leadership and trust between local stakeholders, all of which helps to sustain the systems needed for effective surveillance of many different diseases.

Furthermore, by looking at ongoing disease problems and developing a better understanding of the local context, and how and why people respond to diseases in the way that they do, we can gain insights that apply far beyond the initial target disease. This approach will help to improve the surveillance of EIDs globally whilst also contributing to broader global goals for development.

One Health approaches are particularly effective as they take into account how different local factors, such as human, animal, environmental and socio-economic health all depend on each other. By understanding these interdependencies, it is possible to suggest effective and long-lasting solutions for disease surveillance.

One health at Glasgow

This paper is based on the combined experience of all of the academics involved who have spent over a decade working in One Health. As Dr Jo Halliday, lead author of the article explains, the breadth of knowledge and experience underlies the ideas put forward.

“The collective of researchers working on One Health in Glasgow is unique in its interdisciplinary nature. Our combined expertise together with the belief that everyone has something to contribute of merit, both in their own field and through contributing suggestions to someone else’s, is really quite unusual.”

Dr Jo Halliday

Ebola spread rabidly due to a combination of delays in detection and poor public health capacity

Mobile phone technology can be utilised in the surveillance of disease