Vampire bat rabies in Latin America

Tracking the transmission of a zoonotic virus

Glasgow scientists are conducting world-leading research on vampire bat rabies in Latin America. They are trying to find out how the virus travels across the continent, and further our understanding of virus cross-species transmission in general.

The work is led by Dr Daniel Streicker, an infectious disease ecologist from the Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health & Comparative Medicine and MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research.

The Streicker Group looks at the way pathogens are transmitted between species, with the aim of better understanding the ecological and evolutionary factors that will allow us to prevent disease in the future. Their findings answer fundamental scientific questions as well having real-world implications for public health, agriculture and wildlife conservation.

The group focus their work around bats, a significant species for both emerging and established zoonotic diseases. Much of their field work centres on Peru where there is a high frequency of contact between vampire bats and the humans and livestock they feed on.

The research has been funded by both the Wellcome Trust and The Royal Society.

Bat rabies in Latin America

Vampire bats exist solely in Latin America, between northern Mexico and northern Chile. They are the main cause of human deaths from rabies in the region, spreading the virus through the bite they inflict on their victim in order to feed on their blood.

The vampire bat rabies virus (VBRV) has proven particularly deadly for communities in the Amazon where the rate of rabies infection could up as high as 1 per cent per year. Livestock are also affected with deaths from rabies causing farmers $30 to $50 million annually. In Peru, rabies is the primary disease reported in livestock and a source of serious concern for farmers.

There is also now evidence that rabies is spreading to areas that were historically free of the disease. Up to 12 new governmental districts have become infected on average per year. The virus tends to invade new areas in waves that advance at between 10km and 20km per year. This advance is stalled only by mountains that are taller than the altitudes at which bats thrive.

Since the 1970s, governments in Latin America have attempted to deal with the problem through bat culling using a poisonous paste that is spread among bats by grooming. Yet there is no substantive evidence that this has been effective. Instead the problem of bat rabies appears to be getting worse.

A cattle farm in Peru

What are Glasgow researchers doing?

Working between Glasgow and Peru, Dr Streicker and his team are conducting a number of research studies into the ecology and transmission dynamics of rabies in vampire bats.

Some of the questions they are seeking to answer include: is culling an effective tool for the control of VBRV in Latin America? What ecological and evolutionary factors govern the diversity of viruses in bats and which of these pose the greatest threats to domestic animals? And could bat vaccinations be an effective disease control strategy for rabies?

The scientists use a variety of tools in their research including field ecology, molecular phylogenetics, mathematical modelling, metagenomics and bioinformatics.

Forecasting the spread of the rabies virus

By conducting genetic studies tracking the movement and social networks of hundreds of bats across South America, Dr Streicker and his team have made some significant discoveries about the spread of VBRV across the continent.

The researchers used nuclear, mitochondrial and viral genetic markers of both bats and rabies to link population pattern levels of bat dispersal to pathogen spatial spread.

Their research revealed that rabies has recently spread between geographically isolated bat populations, infecting new areas of the continent. The DNA analysis of the bats indicated gene flow across the Andes Mountains connecting the Amazon rainforest, where rabies is endemic, with the South American Pacific coast, which had previously been rabies-free.

This has enabled the scientists to forecast that there will be a future outbreak of bat rabies on the Pacific coast of South America by June 2020.

This genetic forecasting has been corroborated by the reports of VBRV outbreaks that occurred in livestock after the genetic data had been collected which showed that rabies was indeed travelling towards the Pacific coast, along the routes predicted by the genetic analysis.

This predicted outbreak of rabies could have major consequences for public health, agriculture and wildlife conservation in this area.

“If rabies continues to traverse the Andes and arrives to currently uninfected vampire bat populations on the Pacific coast, this will have important practical implications for rabies control programs in Peru, and potentially Ecuador and Chile, while also creating novel opportunities for rabies to be transmitted to new species that are fed upon by bats, such as sea lions, which could cause new risks for public health and wildlife conservation.”

Dr Daniel Streicker

The most recent findings also reveal how the rabies virus is spread. Analysis of the bat genetic data revealed a differentiation between male and female bat dispersal across the continent; where as female bats remain sedentary, male bats tend to traverse the continent in search of a mate.

The movements of the male bats match the movements of the rabies virus which suggests that dispersing male bats spread VBRV between genetically isolated female populations. This has essentially created a corridor for rabies to migrate across the Andes.

“These results are important because they identify sex-biased dispersal as an underappreciated mechanism underlying the invasion of pathogens across landscapes. Sex biases in dispersal are ubiquitous in animals, so similar mechanisms could be an important factor shaping the spread of other pathogens through wildlife populations such as White Nose Syndrome or Ebola virus in bats."

Dr Daniel Streicker

Ongoing research

In order to apply their findings to improve rabies control in Latin America, the team is now studying when and how far male bats disperse and whether existing or new technologies could be used to target this key group for rabies spread.

However, there are still many more unanswered questions which the Glasgow scientists hope to tackle:

“These results show how host and pathogen genetic tools can help to understand and anticipate the spread of disease, but it is unclear why viral invasions are happening now. Is rabies a relatively new disease in vampire bats that is slowly spreading to the fringes of the bat population? Are environmental changes triggering mixing of historically isolated bat populations, or some combination of the two?”

Dr Daniel Streicker

Ineffectiveness of culling

The Streicker group have also been at the forefront of research highlighting that culling of bats is an ineffective way of dealing with the virus. Culling is generally targeted at colonies that are known to already have the virus. This however targets adult bats that are already immune and furthermore provokes bats to move to different roosts therefore quickening the spread of the virus.

The researchers are currently investigating this theory by analysing data from a large scale culling programme run by the Peruvian government to discover whether culls reduced rabies deaths in livestock or accelerated the spread of rabies by disturbing the social structure of bats.

Dr Streicker with a vampire bat

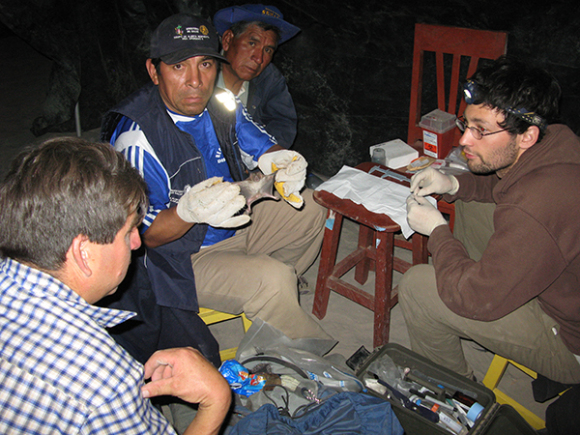

Dr Streicker and project workers in Peru

Impact of research

Though the predictions of a rabies outbreak on the Pacific coast are potentially hugely problematic for the countries affected, one positive outcome from the team's research is that it does give governments time to put preventative measures in place, including vaccination campaigns for the people and animals in the epidemic's path. The Streicker group are now working with Peruvian farmers and public health agencies to implement intervention strategies for communities that are predicted to be hit by rabies.

Bat Rabies as a model for virus transmission

Studying rabies in vampire bats provides a useful model to understand virus cross-species transmission in general. Bats are the animal most associated with viral emergence. As well as rabies, they have been implicated in the spread of many other viral pathogens including the SARS coronavirus, filoviruses and even the Ebola virus. Unlike other bat rabies viruses' though, rabies is constantly transmitted from vampire bats to livestock. This means the researchers are able to study the actual event of transmission between species, which is typically very difficult to observe. Dr Streicker's work is therefore providing the beginnings of a tractable model to understand how and why viruses jump from one species to another.

Why Glasgow?

The University of Glasgow has played a key role in this research. The Centre for Virus Research at Glasgow represents the largest grouping of human and veterinary virologists. It is a hub of collaborative research with scientists working on a diverse array of viruses across human, wildlife and livestock. This creates a unique setting that allows powerful insights into zoonotic pathogens such as the rabies virus.

National Geographic emerging explorers programme

In 2015, Dr Streicker was named as a National Geographic emerging explorer. The programme recognises and supports early-career gifted and inspiring adventurers, scientists and innovators. He explains more about why bat culling is ineffective and other possible options for bat rabies control in his talk for National Geographic.