Thinking the unthinkable

Published: 29 June 2020

COVID-19 has shown us that no one knows what is coming, or what we might need to be prepared for. In this article, Dr Helen Baxter discusses how thinking the unthinkable can help policy and communities become more resilient to emergency situations.

Dr Helen Baxter, University of Glasgow

The challenges the National Centre for Resilience (NCR) seeks to help our responders and policy makers cope with and to make Scotland more resilient to; natural hazard emergencies, pandemic recovery, the effects of climate change, all have implications for every aspect of society and impact every element of our lives. This makes them complex and messy, but more than this, they are unpredictable. We know that these challenges will appear and do exist, but we can never truly predict the outcome. We don’t know what their impacts will be, the extent of their effects, where they will strike, what or who will be affected or how badly. Resilience is having the capacity to respond well to these unpredictable events, so that our society and natural environment can thrive and enable us to achieve our ambitions, despite what the world throws at us.

One of the major challenges of resilience is that, particularly for resilience practitioners across all sectors, the wider population is unaware of many aspects of their work, especially when emergencies are geographically localised or have low-level impacts. Creating resilience takes constant sustained effort, constantly reviewing, assessing risks, learning and developing, maintaining resources, upgrading and renewing infrastructure, developing new skills and training people. That’s not to say that people are not touched by these events, of course they are, no more so than now with COVID-19 and earlier this year with the impacts of storm Ciara[1] and Dennis[2].

The main problem with resilience is it requires preparing for things that you hope won’t happen and which you cannot predict. This means the work that goes into resilience is done in the background and with very little acknowledgement, until it’s needed, at which point it can often become a blame game rather than a thank you. This can lead to both positive and negative consequences.

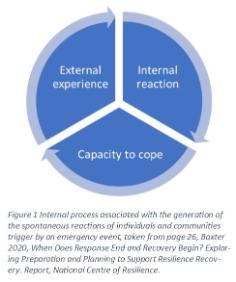

One of the hardest things to manage during an emergency event, and in the immediate aftermath, is the temptation to appear to be doing something, to “firefight “criticism. This is why I think that we should not only be preparing our responses to emergency events but also preparing for recovery. Both practitioners and academics who work in the field of societies’ resilience need to be freed up to think the unthinkable, a strategy which served Shell[3] well in the 1970s. We need to move away from short-term fixes and sticking plaster solutions, which do very little to achieve anything in the long-term. To do this requires time and space, using approaches such as scenario planning. This work needs to be kept up-to-date, constantly evolving, and acted upon because the point at which it’s needed most, is also the time at which our resources and capacity are under most strain (figure 1) and least able to cope with the demands this sort of strategic thinking requires.

However, many sprigs of hope and useful initiatives have developed during and in the aftermath of emergencies across the UK. Organisations have grown from grassroots initiatives and individuals and communities are actively involved in; engaging with resilience practitioners, taking ownership, campaigning, and driving forward solutions and new ways of developing resilience. Organisations such as the Scottish Flood Forum[4] support these groups and provide valuable resources to empower communities and individuals to develop their own resilience, not only to flood events but to other natural hazard emergencies. A challenge for resilience practitioners and policymakers is to work with any spontaneous groups which emerge, maintaining their momentum and enabling them to develop and become part of the long-term recovery process.

In striving to be resilient the first thing to note is that resilience is not an endpoint, it is a process and the process itself can be positive. Second it is important to understand that resilience also requires the support of, and access to, external resources. It is not about battling on alone, again this has been made starkly evident in the response to the COVID-19 outbreak, Government systems and structures are necessary to support individuals and businesses to survive through a crisis.

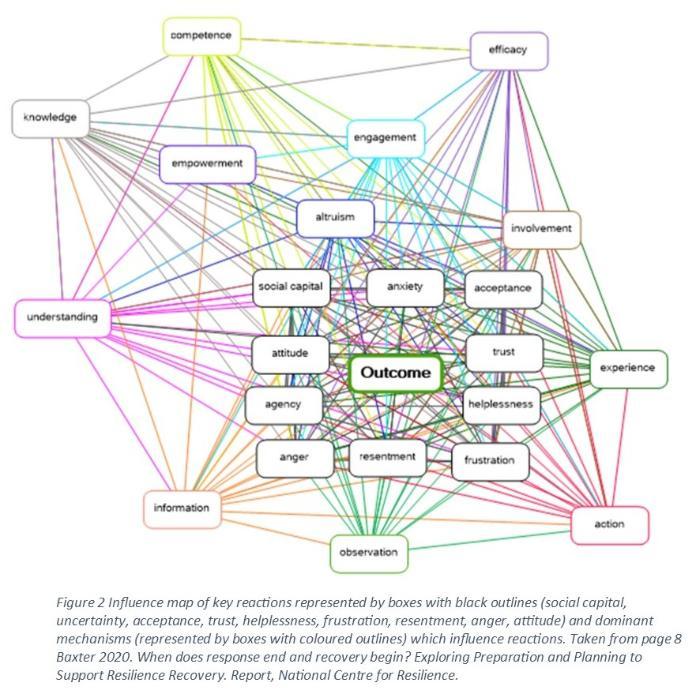

The concept that resilience is about working in partnership with communities and recognising the invaluable resource that these communities possess is largely accepted in Scotland particularly in a policy arena predominantly concerned with natural hazard emergencies and community resilience[5].This attitude has not necessarily transferred to other policy areas though. In the past the solutions to the problems which arise, either directly or indirectly, due to crises such as pandemics, have been assumed to reside beyond most people’s direct experience and understanding. This can be seen in the way in which some politicians and others have, arguably, mishandled some elements of communicating[6] with the public. Based on findings from my own recent research[7] this has the potential to undermine the UK’s future resilience to crises and our ability to recover from the impacts of COVID-19. I identified 12 mechanisms (efficacy, engagement, improvement, competency, altruism, action, observation, knowledge, information, understanding, experience, empowerment) which are a necessary part of a community’s ability to respond to a natural hazard emergency. They are also fundamental to a community’s recovery from a crisis and the potential future resilience of that community. All these mechanisms are interrelated and affect one another. Undermining any one of them will have an impact on how individuals react to events.

It is important that those developing strategy, and communicating it to us, recognise that there are multiple mechanisms at work which we are all exposed to and influenced by, as can be seen in figure 2. That we, the population, are made up of individuals who possess varied skills, and knowledge, and have access to multiple sources of information (accurate and inaccurate), all of which influence our reactions to the crisis over time. This is important because how people react affects their capacity and willingness to work with the experts and professionals and thus their resilience and ability to recover, be it from a flood or a pandemic.

My experience working with resilience practitioners and those involved in community resilience has taught me that the most important thing about resilience is bringing together different types of knowledge and understanding to develop solutions. This empowers communities and individuals to work with specialists, to use scientific expertise and evidence-based solutions along with local knowledge, and apply it to an understanding of what is important to different communities. We all have a role to play in the success of the overall response to COVID-19 and the process of rebuilding our resilience as part of the recovery process. We need to be thinking the unthinkable now, and prepare for a long recovery, because one thing we know for sure is that we cannot predict what happens next.

It is only through working together and using the best of what we have, across a variety of diverse sectors, which will enable us to come together and consider strategically what recovery might look like. To embark on the process of responding well to unpredictable events, requires building trust across society, recognition that there are competing priorities, and that there is no right answer. We need to use the different types of the knowledge and expertise that we have collectively and recognise that our understanding is constantly changing and developing. This is a complex challenge and one which we must engage with if we are to not only survive, but thrive as a society.

[1] https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/metofficegovuk/pdf/weather/learn-about/uk-past-events/interesting/2020/2020_02_storm_ciara.pdf

[2] https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/metofficegovuk/pdf/weather/learn-about/uk-past-events/interesting/2020/2020_03_storm_dennis.pdf

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162511001740

[4] https://scottishfloodforum.org/about-us/#what-we-do

[5] https://www.readyscotland.org/ready-government/resilience-division/

[6] https://theconversation.com/dominic-cummings-and-boris-johnson-have-lost-control-of-the-fear-factor-139237

[7] http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/215851/ Baxter, H. (2020) When Does Response End and Recovery Begin? Exploring preparation and planning to support community’s resilient recovery. Project Report. National Centre for Resilience (NCR).

First published: 29 June 2020

<< Blog