Resilience is everywhere

Published: 30 July 2020

The term resilience seems to be everywhere, but how do you know if you are resilient?

Elliot Meador, PhD

Rural Policy Centre, Scotland’s Rural College

Resilience thinking seems to be everywhere these days. There are UK-wide governmental policies to help promote resilience in local communities.[1] There are pushes in Scotland to promote resilience in the face of emergencies and natural disasters.[2] Cyber-resilience is promoted to help protect people from the perils of online hackers.[3]

My daughter's primary school teaches resilience as part of their curriculum to highlight the "importance for our wellbeing on how we perceive, interpret and respond to the events that happen to us”. Resilience thinking has proliferated into the area of rural community and economic development in Scotland and in countries across the globe. With all this talk of resilience and being resilient, the following questions naturally arise: What is resilience? What do I need to be resilient to? And, how do I know when I'm being resilient enough?

If you are having difficulty answering these questions, do not worry, you are not alone.

These questions often plague resilience workers, advocates and academics. It can be difficult to define resilience when so many different groups use the term to describe some phenomena in their particular domain. And these phenomena do not always overlap in a way that allows them to be directly compared.

Getting back to basics

Whilst theories of resilience have shown up in academic writings since the 16th century, many ideas gained in popularity during the early 1970s with a paper by a researcher called Crawford Stanley Holling. Holling's (1973)[4] paper really re-introduced the idea of resilience into the field of ecology. His definition of resilience is complex, and he uses examples based on mathematical modelling to illustrate what makes resilience systems different from those that are not resilient. However, there is one quote from Holling's paper that sums up resilience quite nicely. According to Holling:

But there is another property, termed resilience, that is a measure of the persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between populations} [emphasis added] or state variables. (p. 14)

We can see from Holling's quote above that resilience is strongly linked to relationships, and I would argue that it is the prevalence of relationships between populations that provides the greatest insights into conceptualising resilience for those working in rural community resilience.

Holling is referring to the relationships between populations of flora and fauna in an ecosystem, but this principle applies to people and communities too. With this understanding, we can revisit the questions from above.

What is resilience? The ability for a rural community to absorb change and maintain the relationships between different populations.

What do I need to be resilient to? Anything that could be deemed a disturbance to a rural community.

Both answers stem directly from Holling's definition of resilience, but whilst the first is somewhat straightforward, the second is less direct. One could deduce that really anything could cause a rural community to be less resilient. It is likely for this reason resilience thinking seems to be found in so many different aspects of life.

How do we know if we are resilient?

It is difficult to know with a high degree of certainty that a rural community is 100% resilient. Findings from researchers at Scotland's Rural College (SRUC) and James Hutton Institute (JHI)[5] suggest that it is perhaps better to break resilience into smaller enabling factors, which can more easily be measured through the appropriate means. Using this approach, we can better judge if a rural community might be at a disadvantage to a variety of shocks or stressors.

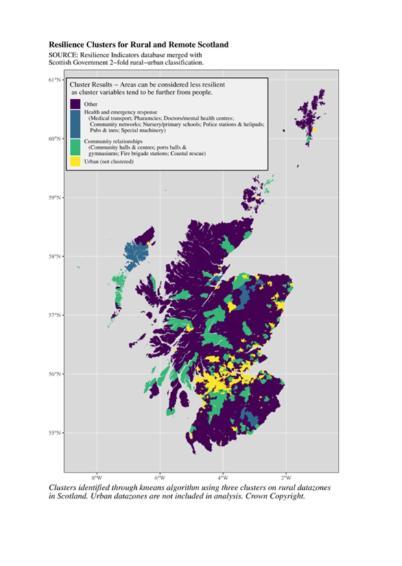

Researchers at SRUC and JHI, with the support of the National Centre for Resilience, have used this approach to map resilience across Scotland, based on about 20 different categories of infrastructure that were all found to promote different types of rural community resilience.[6] This is shown in Figure 1.

Breaking resilience into smaller pieces allows stakeholders to more easily identify potential harmful impacts arising from new shocks. This has the added value of allowing stakeholders from different sections of the community and economy to draw upon their relative expertise in working together to solve large-scale issues. A timely example of this is the impact that Covid-19 is making across Scotland and the world.

Going forward into autumn and winter 20/21, local stakeholders need to have the capacity to work together across many enabling factors if communities are going to be able to absorb the shock brought on by Covid-19 and maintain its pre-Covid relationships.

[1] See here for more information https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/community-resilience-development-framework.

[2] For more information see https://www.gov.scot/publications/preparing-scotland-scottish-guidance-resilience/pages/4/

[3] For more information see https://www.gov.scot/policies/cyber-resilience.

[4] Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 4(1), 1-23.

[5] For more information see https://sefari.scot/research/objectives/local-assets-local-decisions-and-community-resilience.

[6] You can find more information and the report from this project here https://zenodo.org/record/3733112\#.XsvX1xNKjEY

First published: 30 July 2020

<< Blog